The federal opportunity zones program is supposed to incentivize private investment in designated “distressed” areas through various tax breaks. Evidence shows the real benefits go to wealthy investors. Is there a better way?

Opportunity Zones Bolster Investors’ Bottom Lines Rather than Economic or Racial Equity

Lisa Christensen and Lorena Roque

ITEP Policy Brief

December 2019

Opportunity zones (OZ) are designated geographic areas where investments are rewarded with a new set of federal tax breaks created as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). The stated intent of the policy is to alleviate poverty in low-income neighborhoods by incentivizing private investments in designated “distressed” areas through various federal tax breaks. This policy brief provides an overview of how opportunity zones are designed and highlights some of the flaws of the policy, including the detrimental impact opportunity zones have on communities of color.

Under the federal Opportunity Zones program, investors can qualify for various tax breaks on the capital gains income from investments in qualifying opportunity zones.

The Opportunity Zones program claims “to bring investments, jobs, business expansion, and new business development” to economically distressed communities. Fundamentally, the design of opportunity zones undercuts this stated intention. Several studies have demonstrated that investors make decisions about where to invest largely independent of tax incentives,3 which means tax incentives like opportunity zones offer a windfall benefit for projects that would have occurred anyway. This is true in almost every instance; consensus estimates in the academic literature about the responsiveness of business decisions to taxes find that as many as nine out of 10 hiring and investment decisions subsidized with tax incentives would have occurred even if the incentive did not exist.4

While this is likely true for most tax incentives, some states are acting in ways to guarantee this outcome for opportunity zones. For example, state officials in Maryland, when nominating census tracts to be eligible for the Opportunity Zone tax break, identified “distressed areas” based on where developers previously decided to invest in profitable projects that were already underway, rather than selecting “need-based” areas that wouldn’t otherwise attract those kinds of investments.5

To the extent the Opportunity Zones program may influence investor behavior, one likely impact would be to drive investors toward the most profitable projects (high-end condos, luxury hotels, etc.) rather than the ones that are more responsive to the direct needs of the current residents in these communities (for example, grocery stores or community centers). This is because the tax subsidy is significantly larger for highly profitable ventures than for other types of projects.

CONCLUSION

The Opportunity Zones program is fundamentally flawed and therefore unlikely to achieve the stated purpose of promoting greater economic well-being in disadvantaged areas. Rooted in a theory of change that is dubiously grounded in structurally racist ideas and false principles from supply-side economics, the program will benefit wealthy investors while communities in need see no direct benefits that lead to economic equity.

States Should Decouple from Costly Federal Opportunity Zones and Reject Look-Alike Programs

Lisa Christensen and Lorena Roque

Given the shortcomings of the federal Opportunity Zones program and its added potential costs to states, the most prudent course of action is three-pronged:

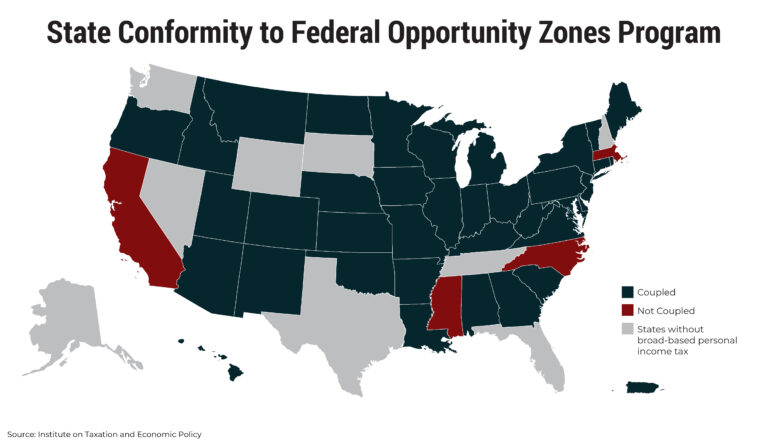

- First, states should move quickly to decouple from the opportunity zone investment income tax breaks that most of them have inherited as a result of their tax codes’ linkages to federal tax law.

- Second, states should reject local proposals that offer even more tax breaks to the investors participating in the Opportunity Zones program.

- Finally, state lawmakers concerned with economically distressed areas should seek to make those investments directly to ensure that the projects are responsive to the needs of current residents. Investments in public transit, education and water systems would create more equitable economies and promote economic growth.

States Should Reject Additional State Tax Giveaways

Since 2018, seven states have enacted (and another seventeen considered) legislation that offers additional state or local tax subsidies for opportunity zone investors. These subsidies have taken three primary forms thus far: tax credits for investments; additional capital gains tax reductions; and property tax reductions for some opportunity zone investments.

Like conformity to the federal opportunity zone subsidies, these additional state subsidies limit the revenue available to states or localities and have been shown to have little or no effect on where investors actually decide to make investments. Making matters worse, in the unlikely event that these subsidies do spur economic growth, their cost makes it more difficult for governments to fund the additional expenditures needed to meet the increased demand for public services that come with economic expansion.

Louisiana and Maryland have both enacted property tax reduction programs for opportunity zones within their states. While business tax incentives for economic development in general have proven to be ineffective, property tax abatements have been shown to be even more problematic. A study by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy found property tax incentives to be ineffective since companies do not choose new locations based on property taxes but on access to a workforce and proximity to markets. More so, these incentives deplete a community’s tax base, depriving funding for local schools, police and fire protection, and street and bridge maintenance.

Maryland’s program allows local governments to offer such reductions if they choose. This creates the potential for counterproductive intrastate competition, whereby various localities within the state’s borders may find themselves competing with each other to offer the largest subsidy. To the extent that this occurs, there will be no net gain to the state of Maryland from this behavior.

Louisiana’s program allows opportunity zones to qualify for property tax abatements in addition to expanding, restoring or improving properties. In its analysis of Louisiana’s property tax freeze program, the state’s legislative fiscal office rightly suggests that it could lead to higher property taxes for individuals and businesses not benefiting from the freeze.

Although only two states have enacted legislation directly related to property taxes within opportunity zones, many opportunity zone investors are likely to reap additional benefits through other preexisting property tax breaks such as TIFs (tax increment financing), which real estate developers can use to abate property taxes.

Rather than depend on these flawed programs for economic development, states should instead take fiscal actions that promote growth in the economy while being conscious of racial equity and economic quality, such as making direct investments in schools and infrastructure. Investing in smaller class sizes and improving access to quality education can boost productivity in the economy. Inequalities that result from relying on local property taxes to fund education can be ameliorated through additional state aid for lower-income communities. Investing in restoring infrastructure, such as improving roads, water and sewage systems, can benefit state economies by spurring jobs while increasing economic quality in the long run. Furthermore, investing in public transit promotes equity by connecting economically disadvantaged communities to more job opportunities.

Conclusion

The federal Opportunity Zones program is deeply flawed. States should decouple from this program as quickly as possible and decline to double-down on its failed trickle-down approach by rejecting proposals to enact additional tax credits for investors of opportunity zones. If states do not decouple, they run the risk of lost revenues as well as larger inequities in the future.

Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy

Comment:

Yes, states should instead take fiscal actions that promote growth… That includes Oregon, where the current property tax system actually discourages growth, fosters disinvestment, and is grossly inequitable. Attempts to reform the tax system by exempting local jurisdictions from Measure 5 and 50 are now underway for the upcoming 2021 legislative session. A constitutional change coupled with a two-rate land value tax system would become a growth engine.

Indeed, why would any state want to shrink the tax base with property tax reductions when the evidence shows this scheme fails to induce investment? Rather, would we not want to expand the tax base and use the premiums for infrastructure and public amenities that attract good businesses? Reducing the tax rate on building assessments and raising the rate on land values has shown to boost building investment. In effect we can convert an entire jurisdiction into an enterprise zone – with no revenue loss that tax breaks cause. Now this is a real ‘opportunity zone’!