HENRY GEORGE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE

Global Dispatches: UK

Land Value Capture Updates

by Joshua Vincent

MANCHESTER WAITS IN THE WINGS

When will people stop thinking that London is the ne plus ultra of the United Kingdom? London is unaffordable.

Manchester was the crucible of the Industrial Revolution; economically, politically, and culturally it could hold its own against London. At its height in the early 20th century, Manchester was the home of British liberalism at its finest.

From the late 19th century until now, the UK saw a long yet fruitless dance with land value taxation. First, Manchester tried to be a champion of LVT, along with Glasgow. The end of the 1st act was a 1921 bill proposing local LVT for Manchester with a rate of 5% (!) on capital land values. Then radio silence. The Conservative Party (a.k.a. the landed gentry) saw[ed] off each opportunity.

The Troublesome Midlands

Manchester’s piping up again in the form of Andy Burnham, the mayor. Mr. Burnham is a new breed, unafraid to confront big bad London and to stand up for the industrial North. Now, Burnham is happily advocating a land value tax:

“I think we’re trapped in a model that doesn’t work particularly well, which is overtaxing people’s work or people’s labour and under-taxing capital and assets,” he explained.

For Mr. Burnham, a land value tax is a solution to this issue. He said: “Land value capture is the way to take a first step out of that [unfair tax system], because you’re not necessarily saying ‘we’re going to come and swipe something that you’ve got’.”

Burnham is not new to the idea: he was on board as a Labour MP for years. And, the mayor is not alone. Political and public support for LVT has been bubbling up in recent years. And the contraction of the British economy and chronically weak leadership at the national level calls for new ideas, and quickly. The British government is quietly collating and validating land values for “policy appraisal.” Commercial, industrial, agricultural and other land values are up for investigation. Stay tuned!

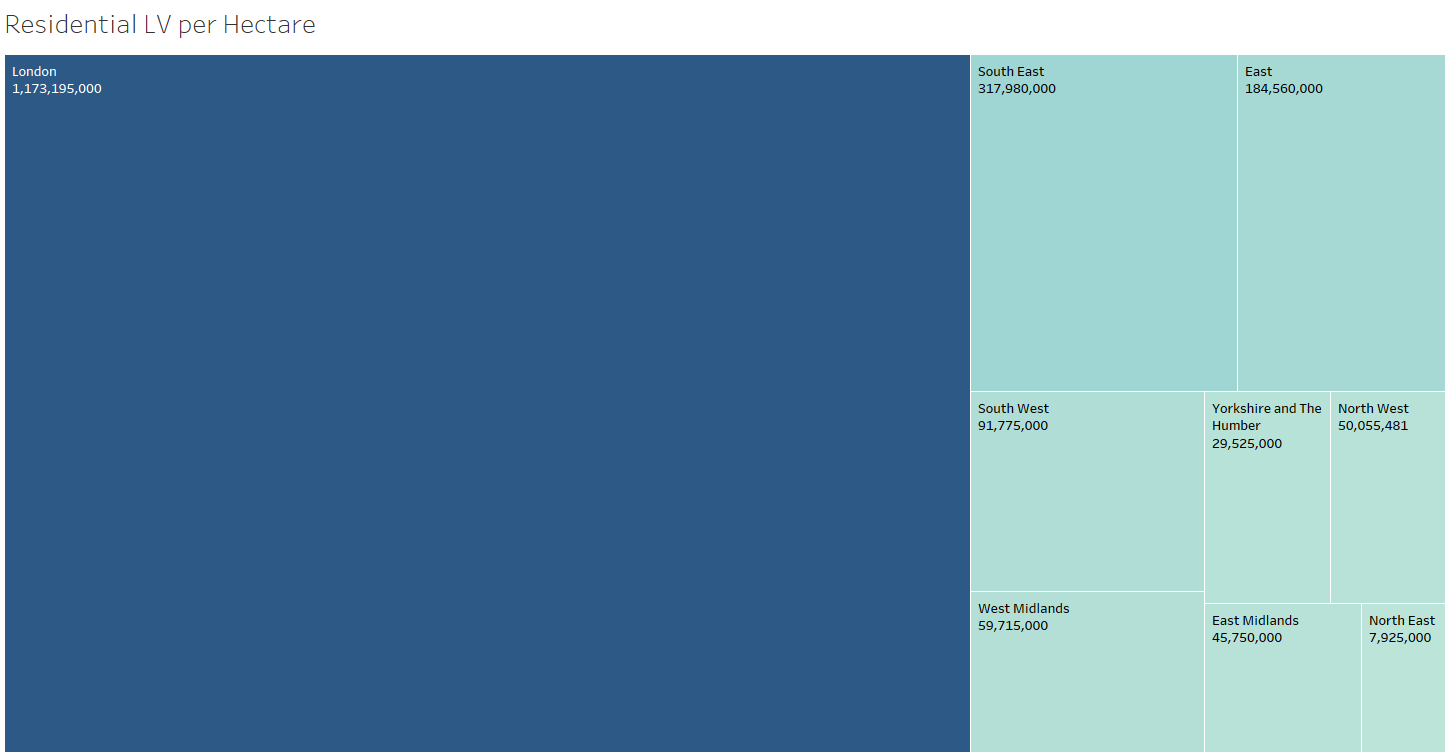

Residential land value per hectare

_________________________________________

Comment:

There is an active land tax movement in the UK. A principal organisation behind it is the Labour Land Campaign, which is advocating on several fronts: “The campaign wants to see unearned land wealth taxed to tackle wealth inequality, solve the housing crisis, to make homes affordable and fund public services.”

On land value capture: “Government and the Mayor of London are keen to capture a greater and ‘fairer’ proportion of the increases in land value which follows transport investment, to unlock the major infrastructure underpinning much-needed housing growth.” “In recent years there has been a re- emergence in political interest into how increases in land value can be fairly “captured” and used to fund investment in new transport infrastructure. There is a recognised link between transport investment and significant increases in the value of land, particularly for land close to a train station. For example, the Jubilee Line extension cost £3.5bn to build. Between 1992 and 2002 it created an unearned uplift of more than £13bn for landowners in the vicinity of the 11 new stations.”

This means that when an infrastructure investment increases the value of land around it a proportion of that increase in value is returned to government.

On housing: The soaring cost of land is also a driving force behind England’s broken housing market. In 1995, the price paid for a home was almost evenly split between the value of the land and the property, but today it has risen to over 70 per cent. Since the most significant cost involved in building a new home is the land it sits on, the price of a new home is driven by the cost of land, and the high cost of land makes it more expensive, difficult and risky to build homes at affordable prices. This then reduces the rate at which new homes are built.

To tackle these issues, we need to get serious about tackling the underlying causes, and one of the ways to do that is through a land value tax. Taxes on land have long been favoured by economists. A land value tax is based on two principles. It taxes the value of land, not the property standing on it. And the value of the land is calculated based on its ‘optimum use’ under existing planning permission, not its current use. These principles confer several advantages over the taxation of property, such as our current business rates. By taxing undeveloped land based on its use value, it penalises those who hold land without developing it, and incentivises development.

Manchester based MP Michael Meacher advanced the idea of a land value tax in his 2012 Guardian article ‘How to kickstart the UK economy’. “I think that land value tax has been hovering over political debate for decades. I think the first mention of it goes back to forty or fifty years. I want to bring it up to the political agenda; I want it to be seriously considered.” Dr Adam Leaver, Manchester Business School, said: “The tax has a supply and demand implication. The price of property is being driven sky high at the moment simply because there is a shortage of developable land. One would prevent more speculative purchases of land if there’s a tax on it. You might see some kind of relaxing of prices if you were to tax the land and therefore much more land might suddenly become available.”