How the 1990’s Oregon property tax revolt resulted in skewed tax burdens is by now well documented. This Oregonian editorial illustrates the problem and the difficulty in finding a solution. The inequity problem really is that bad; but are solutions that elusive? Read on…

Tax breaks for gentrifiers: How a 1990s property tax revolt has skewed the Portland-area tax burden

By Elliot Njus

The Oregonian Business

Updated Apr 22, 2019; Posted Sep 11, 2015

Excerpt:

Tom Lewis says his east Portland neighbors have voted time and again with the rest of the city to raise taxes, but they’ve seen little of that money come back in the form of improved schools, transportation and parks. That’s bad enough. But it also turns out that Lewis and his neighbors are paying more than their fair share of those taxes compared to other parts of the city. “We’ve got ‘sucker’ written on our forehead,” he says.

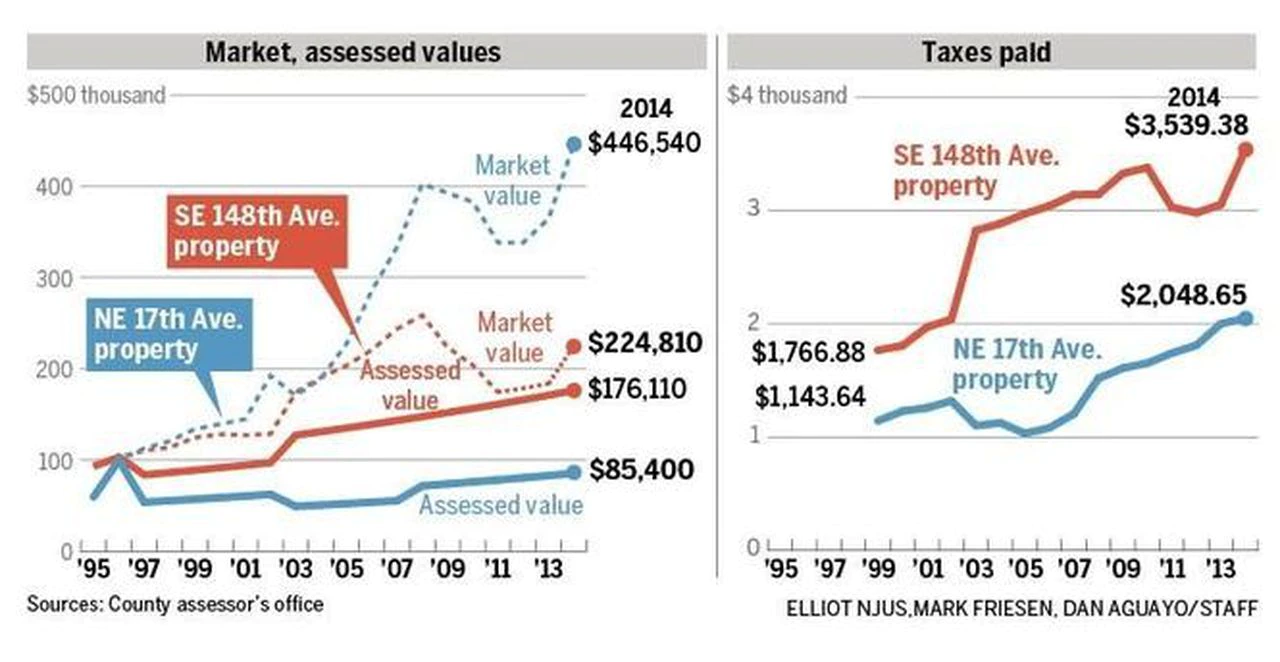

Last year, Lewis’ property taxes came out to $15.74 per $1,000 in value. Across town, a similar house just off trendier Northeast Alberta Street is worth twice as much, but its owners paid just $4.59 per $1,000 in value. Swaths of North, Northeast and Southeast Portland are getting tax breaks while homeowners in east Portland and Southwest Portland pick up the bill. In some cases, residents least able to shoulder the extra burden are being forced to carry more. The median household income in Lewis’ east Portland ZIP code is $35,970, compared to $61,962 near the house off Alberta.

“It’s not fair and it’s not equitable in terms of what we get for our tax dollars,” said Arlene Kimura, an east Portland neighborhood activist. “We’re not even close in proportion to some of the more affluent parts of the city.”… “We’re pricing people out. It’s hard enough for people to come up with down payments and all this stuff. And then to come up with a $2,000 tax bill? And somebody else’s property tax is basically 50 percent of that?”

Oregon’s system has created great inequities, concentrating benefits in gentrifying neighborhoods that have seen fast-rising home values. Other parts of the metro area have seen their relative tax burdens increase.

Oregon’s property tax system has dramatically distorted the tax burden in the Portland area, an analysis by The Oregonian/OregonLive found, pushing responsibility for basic government services off the backs of one set of homeowners and onto others.

The culprit: ballot measures voters approved in the mid-1990s to slow soaring property tax bills. That’s when Oregonians moved away from the traditional standard of taxation in which the amount you pay depends on how much your home is worth. The effect of ballot measure 50 permanently disconnected taxes from present-day property values in Oregon.

Two similar properties in Portland have retained their very low taxable values, established in 1995. The house on Northeast 17th Avenue has quadrupled in value, yet its owners pay lower taxes. The house on Northeast 148th Avenue, meanwhile, has increased in value at a much lower rate. (See graphic below)

Northwest Economic Research Center at Portland State University found that in Portland, properties getting a tax benefit tend to sell for a premium: a dollar of tax savings can amount to an average increase of $33 in sales price. “If you’re going to bid on two houses and one had a lower tax bill last year, you’re going to bid more for the one with the lower tax bill,” said Jeff Renfro, one of the researchers.

At the moment, it appears few recognize the issue or see it as a problem. Lewis, chairman of east Portland’s Centennial neighborhood, says he doesn’t think many of his neighbors have any idea they’re losing out in the current system. “For most,” he said, “it’s just, ‘Let’s see if we can make a living, pay our taxes and get to next year.'”

How could the disparity grow without public outcry over the years? Perhaps the Byzantine nature of Oregon’s tax laws. Even public officials steeped in tax policies admit to getting tripped up by the details of Oregon’s complicated system.

“Oregon’s tax system came in so many steps,” said Joan Youngman, a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in Massachusetts. “Initiatives and tax revolts tend to focus on a particular problem. Every complexity you introduce to deal with one problem gives rise to another problem that gives additional complexity.”

Comment:

What will it take to build public support to change Oregon’s Byzantine property tax laws and repeal Measures 5 and 50? Previous market research on the subject indicates that many voters would be willing to address inequities in the system – provided their own taxes won’t increase. Is it really as simple as that? Homeowners, apartment owners, and businesses also realize that the current tax system not only decouples market values from taxable values, but that it is inherently punitive. It penalizes owners who fix up their properties or add improvements like auxiliary dwelling units with steep increases in tax bills. Now if I’m a responsible owner and want my building to maintain or increase its value, I might well support a property tax fix that is not only more equitable but incentivizes constructive behavior. If that’s gentrification then it’s the kind that one would think should not be penalized.

The Northwest Economic Research Center at PSU recently completed another study evaluating Oregon’s broken property tax system. The study’s data confirms this article’s findings: the average property tax bill for homeowners in outer southeast Portland comes to $12.17 per $1,000 in value; the same measure for inner northeast residences is $7.29 per $1,000 in real market value. The NERC study didn’t just document what we know are inequities in the tax system; it examined a potential solution: a land value tax (LVT). The researchers concluded that LVT as an alternative to the current system is not only more equitable, but also provides a tax incentive to invest in building improvements. This is accomplished through a return to real market value assessments and differential tax rates on land and buildings. Check out Common Ground OR/WA website for a link to the NERC report.