WHO’S GETTING WALKED OVER?

Willamette Week carried Sofie Peel’s story in the October 26 issue about the reaction of Montavilla neighborhood residents to a city proposal to repair long-neglected unimproved streets on 89th Avenue. Portland City Council is refocusing its infrastructure projects on one of the most overlooked parts of town – East Portland. According to the city’s established method for localized construction works, a local improvement district (LID) can be formed, whereby the expense is shared by homeowners and the city. The Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) has to date completed 58 local improvement districts. In this case the LID is mandatory because most of the property in the district is owned by the city which will cover three-quarters of the total budget. Homeowners in the district are obligated for about $47,000 for each property. But many of them who are retired and living on fixed incomes filed an objection, claiming the cost is too much of a burden.

Willamette Week carried Sofie Peel’s story in the October 26 issue about the reaction of Montavilla neighborhood residents to a city proposal to repair long-neglected unimproved streets on 89th Avenue. Portland City Council is refocusing its infrastructure projects on one of the most overlooked parts of town – East Portland. According to the city’s established method for localized construction works, a local improvement district (LID) can be formed, whereby the expense is shared by homeowners and the city. The Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) has to date completed 58 local improvement districts. In this case the LID is mandatory because most of the property in the district is owned by the city which will cover three-quarters of the total budget. Homeowners in the district are obligated for about $47,000 for each property. But many of them who are retired and living on fixed incomes filed an objection, claiming the cost is too much of a burden.

The district homeowners insist they should pay nothing for the upgrades, claiming the city is responsible for public infrastructure. PBOT program administrator Andrew Aebi says local residents have an obligation to the greater good. The city is not going to walk away from this pervasive problem that plagues much of East Portland. So who should pay for these LID projects?

Looking back into Portland’s history we can see who actually financed infrastructure built to service the multitude of subdivisions making up the cityscape. Take Ladd’s Addition for example:

Banker and investor William Ladd acquired land in the city’s inner southeast quadrant in 1878, investing $10,000 in a 126-acre plot. He and his wife Caroline platted the land in 1891. His estate company then paved streets, built sidewalks, and planted trees. The city parks superintendent transformed the street-converging squares into rose gardens. Electric trolley line improved access to downtown. A new water main provided fresh water. The completed subdivision reached a market value of over a million dollars.

There are lessons to be learned from this history. First, the local government likely did not finance most of the city’s local street infrastructure. Second, look at how public investments enhance private market values.

The bureau’s reported response to the Montavilla homeowner’s LID complaint is mostly procedural. But I believe we could shed more light on this problem if we look at the financial implications of the project.

As stated in the article, the Oregon Constitution mandates that cities undertake such projects “based on benefit to property, not based on ability to pay.” These two legal bases for the tax obligations of private citizens are universally acknowledged. Some tax mechanisms are better rooted in the ability to pay principle, like state income taxes; others are better matched to the benefits principle, like LIDs. Here the benefit to a property owner is not only the convenience and safety of street improvements, but rather the direct financial benefit the owner receives.

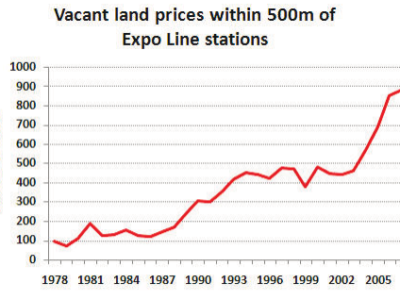

Perhaps the clearest example of benefits received is a proposed rail transit station area designated to become a transit oriented development (TOD). The benefit derived by landowners in the area is the location value. The new transit improvements and accompanying up-zoning not only create accessibility benefits to potential transit riders, but also create monetary value for the owners of nearby properties as the public investment is capitalized into higher land values and new development opportunities.

A tax based on the benefits principle is in essence a quid pro quo, a pay-back for an equivalent financial gain received from a government action. The common term for this is value capture, where the local government as the steward of the public interest retains the right to appropriate from the receiver an equivalent amount of value.

Common Ground – OR/WA has been actively involved in a trend throughout the world, by proposing that a value capture mechanism be employed in the Portland region’s Southwest Corridor, if and when the voters approve funding for the planned MAX light rail expansion. PBOT is well aware of our proposal to use a value capture tool called Transit Benefit Districts (TBD). A TBD is like an LID, whereby a contiguous group of property owners share in the cost of installing new infrastructure supporting the development of TOD by paying a betterment levy in direct proportion to benefits derived from the improvements. The value capture mechanism proscribed here is a mandatory TBD because all stations within a new rail transit corridor identified as TOD centers need to be subject to the same betterment levy methods and procedures.

The fact is, whether it’s a TOD or an LID, adjacent owner’s land values will increase, in many instances substantially. If there are any doubts, take the case of Seattle’s LINK light rail North extension. Median home sales prices in station areas grew by 55 percent, and commercial property prices grew by 149 percent from 2012 over a 5-year period, coinciding with construction of the Capitol Hill station, leading to its opening in 2016. We can assume that price increases are subsumed in land values.

Whether it’s transit station areas or 89th Avenue homes, we can be assured there will be land value premiums to be received.

In February 2020, PBOT broke ground for the SE 80th & Mill LID. Property owners, including Portland Public Schools and 21 residential property owners in the area, were billed $758,505 for this $2.7 million project. Homeowners agreed to the LID because they realized their properties would increase in value, and when their houses would eventually be placed on the market, the increase in sales price they could realize would likely cover the cost of their LID obligation. Quid pro quo.

Whether it’s a TBD or LID, the government, financed by us taxpayers, cannot be in the business of handing out windfalls.

Upon hearing the pushback from homeowners on SE 89th Avenue, City Commissioner Dan Ryan asked if the city could offer exemptions or hardship waivers. It’s understandable that retired pensioners living on fixed incomes would experience a hardship making annual payments of $165 over 20 years. But again, the benefit received from the street improvements plus other location premiums from public amenities like a public plaza on SE Stark, capitalized into land value increments, amounts to real money. Homeowners are already seeing land value increases as home prices have been skyrocketing in recent years (most of that is land value). Over time this is accumulated equity. The proposed LID improvements add even more to that. However, these “unearned givings” cannot be realized until the sale of the home. This is why tax exemptions and waivers are not appropriate, but property tax deferrals are.

Mr. Aebi demurred when the Montavilla residents refused to participate, but added that the city could defer the loan for an additional five years. Technically he is correct to move ahead with a mandatory LID and to state a preference for waiver. Perhaps it would be wise to estimate the land value premiums that the owners can expect to receive, then base the property levies on that. Quid pro quo.

Tom Gihring, Research Director

Common Ground OR-WA