The Washington Post

As Purple Line construction resumes, the fight against gentrification is on

Gerrit Knaap’s group, the Purple Line Corridor Coalition, examines how development coming to future Maryland light-rail stations can be most equitable

By Katherine Shaver

September 30, 2022

Excerpts:

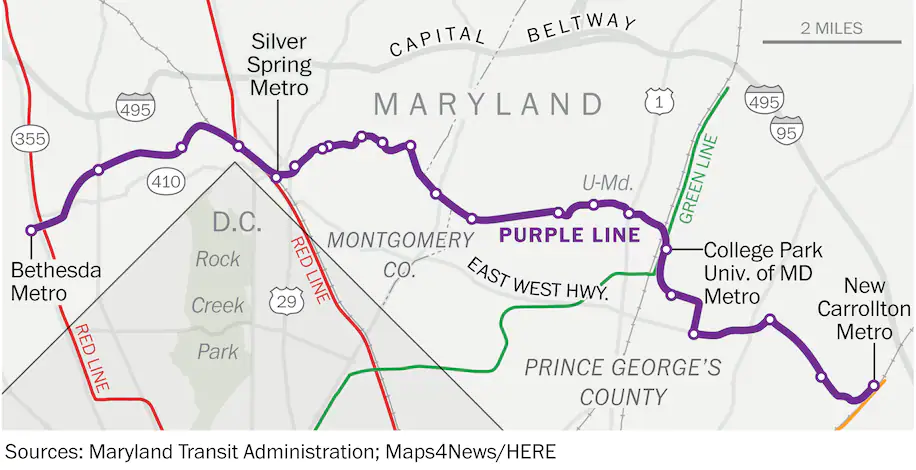

In 2013, four years before construction started on Maryland’s Purple Line, a group of academics, planners, nonprofits and elected officials began thinking about the economic development the 21 rail stations would bring — and the inequities likely to follow.

State and local officials have said they hope the Purple Line will transform aging, auto-dependent suburbs, particularly in Prince George’s County, into vibrant hubs of new apartment buildings, stores and restaurants — all within walking distance of light-rail stations.

But the public-private group known as the Purple Line Corridor Coalition, has long eyed cautionary tales from other new transit lines. Without intervention, the coalition says, rising land values around stations lead to higher rents and price out local businesses and residents, including lower-income workers most in need of faster, more reliable mass transit.

The coalition, based at the University of Maryland’s National Center for Smart Growth Research, has analyzed how to preserve affordable housing and small businesses along the 16-mile rail alignment between Prince George’s and Montgomery counties.

As major construction on the long-delayed Purple Line resumes this fall under a new lead contractor, The Washington Post spoke with Gerrit Knaap, the coalition’s founder and the smart growth center’s director. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Why did the coalition begin focusing on gentrification issues in the Purple Line corridor so long before the light-rail line would open, and even four years before construction started?

Knaap: It takes a lot of lead time to change the urban fabric. Land market changes take a long time. Price changes occur more quickly. We’ve begun to see housing prices and rents rise in the Purple Line corridor already and have for a number of years. And obviously if you’re going to try to preserve affordable housing and small businesses, you need to do that before prices start to rise too quickly. Therefore you need to get a head-start on it, not to mention you need to have the policies and resources in places to help businesses and residents during the construction period.

Q: What was it about the Purple Line corridor that prompted concerns about gentrification?

Knaap: The Purple Line corridor is extremely diverse in terms of income levels and economic prosperity. There are some very low-income communities right on it. In fact, I give credit to [immigrant advocacy group] CASA for addressing the gentrification threat, and we teamed up with them very quickly.

Map of Purple Line Corridor in Maine

Q: A lot of us think about transit-oriented development as high-rise apartment or condo buildings with coffee shops and high-end stores at the ground level. Is that the kind of development you see coming along the Purple Line, or will it be different in these more suburban locations?

Knaap: No, it’s definitely going to be different. You’re not going to see high-rises at these Purple Line stations in between the Metro stations. That’s just not going to happen. The market isn’t there for it and even the regulatory environment wouldn’t allow it currently. It’s going to be more mid-rises, more smaller scale. We’re going to be thinking about strip malls. I don’t think it’s helpful to have strip malls near Purple Line stations. If we can get them to increase to two-, three- or four-story density, that might be a good thing. And, of course, you’d want them to be as mixed-use as possible. I don’t think anyone envisions the Manhattanization of the Purple Line corridor.

Q: How can lower-rent housing be preserved as demand to live near future rail stations increases? How difficult is that to do?

Knaap: It’s very hard and there’s not one answer. You have to be a bit opportunistic. One way is to preserve the existing affordable housing stock, which you can do by buying it or having rights-of-first refusal policies. … On one hand you’re trying to preserve the existing housing stock. On the other, you’re trying to increase the housing stock through affordable housing construction. Another way is to try to change the existing development regulations, either by upzoning [with more density] or by policies that enable middle-income housing to be competitive.

______________________________________

Comment:

The Purple Line Corridor Coalition has identified the foremost problem in the rail corridor. Without intervention, rising land values around stations will lead to higher rents and price out local businesses and residents. It happens in every case of a new rail transit line: a rush to control property in the vicinity of stations marked for transit oriented development, in anticipation of windfall gains following rapid land value increases. What intervention is needed to prevent landholding speculators from passing on the burden of high priced land to future residents and businesses?

Mr. Knapp’s “opportunistic” solution is to preserve the existing housing stock, and simultaneously increase the housing stock through affordable housing construction. The means suggested is a law of ‘right of first refusal’, where affordable housing units that are being sold are reserved for qualified non-profit housing corporations (such as Community Land Trusts) which insure continued affordability over the long run. And of course, in a transit oriented district up-zoning to higher density housing types would normally be expected. These are worthy efforts, but they alone would have limited effect on producing affordable housing.

There is an unmentioned intervention that would add immeasurably to the “policies and resources in place” needed to deal with the rising land values around stations. Value capture is a mechanism by which all or a portion of the financial benefits to property owners generated by geographically targeted public capital investments are appropriated by a local public authority. In the case of the Purple Line corridor, benefits accrue in the form of land value uplift attributable to the location of rail transit stations. Therefore it is fair that this value premium should be returned to the public through the employment of a special assessment district. Land value capture is becoming widely recognized as the preferred tool for financing transit-oriented development. Capturing land value increments has a dual purpose: (1) to finance public place-making capital improvements that support TOD; (2) to avert windfall gains and impede land speculation in station areas.

Tom Gihring, Research Director

Common Ground – OR/WA