Cities across the country are proposing up-zoning laws to combat the housing crisis. This might actually work – if coupled with a land value tax. Read on…

Will Up-Zoning Neighborhoods Make Homes More affordable?

Cities and states across the country are proposing new up-zoning laws to combat the housing crisis. Will they work?

By Diana Budds

Jan 30, 2020, 1:00pm EST

Excerpts:

Housing affordability is a growing issue in America, and there’s a battle over how to fix it happening on blocks across the country. Zoning—the rules that govern how cities use their land—is on the front line.

Between 1986 and 2017, the median price of single-family housing in the U.S. rose from 370 percent of the median U.S. household’s yearly income to 410 percent, according to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Eleven million American households spend more than half their paychecks on rent and utilities.

Recently, policymakers at the state and local levels across the country have zeroed in on a culprit: zoning that limits development to single-family detached houses in large swaths of America. Zoning now makes it illegal to build anything other than a detached single-family home on most residential land in many of the American cities. Detached, single-family homes account for 94 percent of all land zoned for residential use in San Jose, California; 81 percent in Seattle; 77 percent in Portland, Oregon; and 70 percent in Minneapolis.

From the east and west coasts to the Midwest, lawmakers are beating the drum for up-zoning, which means changing single-family zoning codes to allow taller and denser housing, like duplexes, triplexes, accessory dwelling units (ADUs), and apartment buildings. In the last few years, up-zoning legislation has been introduced or passed in California, Oregon, Washington, Seattle, Minneapolis, Nebraska, Virginia, and Maryland. But is up-zoning enough to alleviate the housing shortage?

What is up-zoning and why are lawmakers proposing it?

In response to the growing housing affordability crisis, policymakers in many cities and states are trying to figure out how to add more housing. The challenge is that buildings occupy most of the land in cities. Up-zoning opens up the capacity of this land for more housing. There’s also a climate case for up-zoning: Building housing closer to transportation and jobs means people have to travel shorter distances to work and shop, lowering vehicle miles traveled and potentially allowing them to use public transportation and walk in lieu of cars.

As Christopher Herbert, managing director of the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, explains it, as long as there is sufficient demand for housing, developers will build. The price of land, the cost to build a home, and what the market is willing to pay for a home all factor into a developer’s math. If the cost of land is low enough that the developer can earn a profit, then the developer will build. By increasing the number of units that can be built on each parcel, up-zoning lowers the cost of land per unit. But there’s a caveat.

“There’s a hope that if we up-zone this land worth one million dollars and now we can put two units on it, the land cost is $500,000 [per unit],” Herbert says. “But as soon as you tell me I can put two units, it’s going to affect the price of land since it becomes more valuable.”

A study published in January 2019 in the journal Urban Affairs Review analyzed the impact of new up-zoning policies Chicago passed in 2013 and 2015 that allowed denser housing near transit stops. The study concluded that over a five-year timespan, up-zoning didn’t increase housing supply, but it did increase land values

Proponents of up-zoning argue that allowing denser construction will encourage more housing supply, and as more supply enters the market, housing will become more affordable through the filtering effect, where even high-priced new housing can lower rents for lower-income residents by reducing the competition for homes. One challenge with this approach is that added capacity doesn’t necessarily translate into added construction because developers don’t always choose to build.

According to Virginia Delegate Ibrahim Samirah, the current way affordable housing is constructed in his state isn’t working. “There are a lot of very expensive solutions to our housing crisis in Virginia, and it seems like throwing money at the problem is the solution,” he tells Curbed. “People are advocating for Housing Trust Fund money to develop affordable housing and it’s led to very modest results in affordable housing. The same with incentivizing developers to set aside affordable units.”

Does up-zoning work?

Because up-zoning of single-family residential land is a relatively new phenomenon there are few studies that analyze the effects.

“Oregon and Minneapolis are going to be our guinea pigs,” says Jenny Schuetz, a Brookings Institute expert on urban economics and housing policy. “Now that they’ve got this new legislation, how quickly does the housing market start to respond? Are we seeing increased housing of the kinds that we wanted?

According to Schuetz, the value of up-zoning lies in areas where land value is high, where developers already want to build, and where additional units will generate a profit for whoever owns the land.

“A lot of cities are saying let’s open the spigots, we’ll build so much housing we’ll get to the point where we get vacancies,” says Christopher Herbert, managing director of the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. “But If developers see vacancies rise they will stop building…It’s the nature of our capitalist system.”

Who supports and who opposes up-zoning?

While most people can agree that there’s an affordable housing shortage, there’s disagreement on how best to address it.

In Oregon, some cities expressed concern about the extra pressure on their infrastructure. Arguments opposed to new housing frequently cite changes in “neighborhood character” as reasons why such legislation shouldn’t be passed.

“The idea of ‘preserving neighborhood character’ is nicely vague enough that it can cover lots of things without being very explicit,” Schuetz says. “They’re worried about changing the feel of the neighborhood with taller buildings. But for many people this is also the type of person who lives in the neighborhood. If it’s white and wealthy and mostly nuclear families, there are places that would like to keep that. And they don’t have to say we want to keep out black people, they just have to say ‘we want to preserve the neighborhood character.’”

Housing advocates who fear displacement and gentrification—like Oakland’s Moms 4 Housing—are also concerned about changes to neighborhood character up-zoning might accelerate.

California state senate candidate Jackie Fielder is running on a social justice platform. Housing is a major part of her agenda and she signed the Homes Guarantee pledge, which includes repositioning housing a human right rather than a commodity. She has criticized SB 50 for its reliance on trickle-down economic theory, its focus on market-rate housing, and its lack of attention to affordable housing creation and protection for vulnerable communities.

“We need to build for need—not for profit,” Fielder recently said. “And with the fifth-largest economy in the world, with 157 billionaires worth more than $700 billion combined, California has all the resources we need to do more.”

The future of up-zoning and the housing crisis

At the heart of the up-zoning debate is a seemingly simple question: Can we provide more affordable housing solely by allowing for more construction? But the real question is much deeper: Can we build our way out of a crisis that’s the product of an economic system that extracts as much as it can from most individuals in order to enrich the few?

Up-zoning is challenging a symbol of American homeownership—the single-family home—that has been subsidized by the government for over a century, and that remains a major source of wealth for millions of people. The real debate around up-zoning is an ideological reckoning over whether housing is a commodity or a right. Solutions that fail to address this question cannot solve the housing crisis.

“We have got to de-commodify [housing],” Fife says. “We’ve got to take the profit motive out of essential needs. That’s the biggest fight. We need to figure out other ways for investors to make money that don’t rely on the things that people need to survive. We shouldn’t be able to commodify air, water, and housing.”

Comment: (This is a much-abbreviated excerpt of Diana Budd’s wide-ranging article.)

Certainly, up-zoning alone is not going to solve the housing crisis in the nation’s rapidly growing cities. Christopher Herbert cites an important clue to solving the following dilemma. “If the cost of land is low enough that the developer can earn a profit, then the developer will build. Up-zoning lowers the cost of land per unit.” But here’s the rub: The cost per unit may be potentially low enough to reach the decision to build, but the act of up-zoning itself gives additional value to the land due to its enhanced income potential. “As soon as you tell me I can put two units, it’s going to affect the price of land since it becomes more valuable.” So up-zoning to allow multifamily units is more efficient, the boost in land cost cancels the economic advantage. The solution? De-commodify housing by phasing-in a land value tax. Taxing land more heavily dampens the speculative increase in land price.

But is that where we simply walk away from the dilemma? If we do, we concede that up-zoning inevitably results in giveaways for landowners who either (i) generate even more profit if they build luxury units, or (ii) reap windfalls through the speculative holding of land. Then we fall back to the default of raising more public funds for housing subsidies. As Delegate Samirah stated: “There are a lot of very expensive solutions to our housing crisis in Virginia, and it seems like throwing money at the problem is the solution.”

There is a better solution. The most simple and effective way to drive down the cost of up-zoned land is to first introduce a general land value tax as an alternative to the ad valorem equal rate property tax. Placing a high tax rate on land assessments and a low rate on building assessments produces two complimentary incentives: to exert downward pressure on the selling price of a land parcel, and to lower the effective cost of development. And it is true: “the value of up-zoning lies in areas where land value is high.” The higher the land values the stronger the incentives. LVT is in fact a market approach to “de-commodifying” housing. If housing is a right, then we have to retreat from the notion that home ownership is a major source of wealth-building.

Yes, up-zoning can work to boost housing production if it is coupled with incentive taxation.

Tom Gihring, Research Director

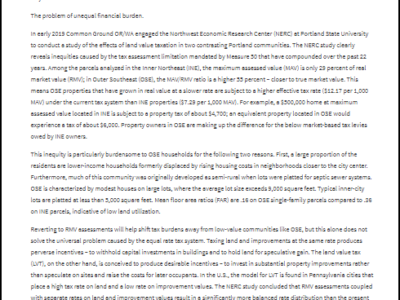

Common Ground OR-WA