February 15, 2024

By: Daniel Hauser

Excerpts:

Two recent proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors would erode the principal source of revenue for local governments — property taxes — and worsen existing economic and racial inequities. The senior property tax freeze proposals come in the form of an initiative petition for the 2024 ballot (IP 10) and a legislative resolution (Senate Joint Resolution 202) in the 2024 legislative session. Property taxes are a primary source of funding for local services, such as libraries, public safety, and fire departments.

To determine how much a homeowner owes in property taxes, a taxing district applies a tax rate to the home’s “assessed value.” Both proposals lock in the “assessed value” of the home for eligible properties. A property is eligible for the property tax freeze “when at least one person is 65 years of age or older on or before April 15 immediately preceding the beginning of the property tax year and, either individually or jointly, owns and occupies the home as their primary

The freeze ends when the owner who is a senior dies or moves to another primary residence. The freeze proposals also provide that the assessed value of the home is to be reset to what it would have been in the absence of the freeze upon the sale or transfer of the property, or if certain improvements are made to the property.

Revenue Loss

The revenue loss that would ensue from the enactment of either of the proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors would grow over time due to two factors: the structure of the policy itself and the aging of the population. As such, over time, it would eat away at the main source of revenue for cities, counties, school districts, library districts, fire districts, and more. About one-third of the funding for schools comes from local sources, primarily property taxes.

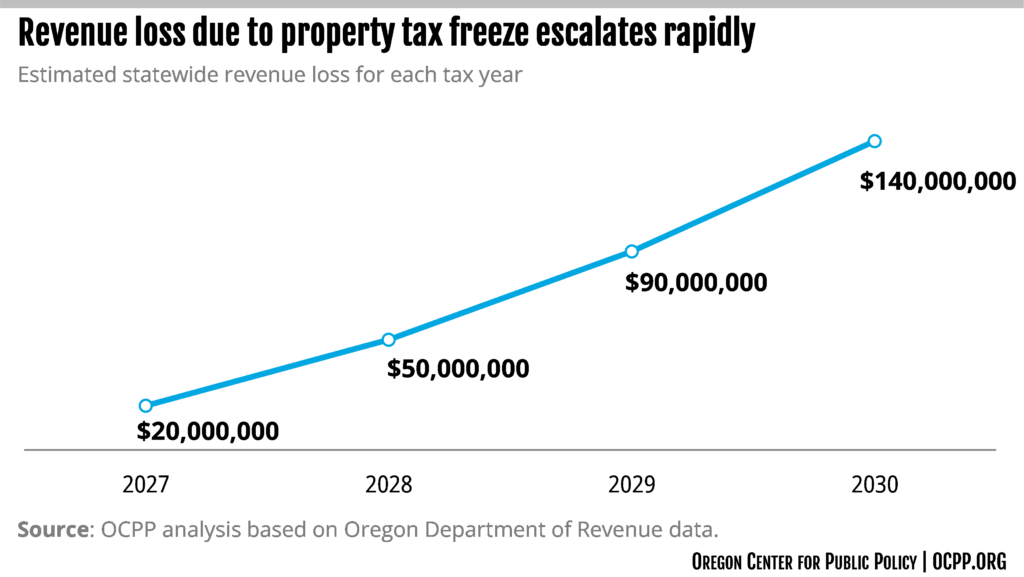

It is difficult to arrive at a precise revenue estimate based on publicly available tax data, but a conservative estimate of the cost of either of the proposed property tax freezes in the first year after taking effect (tax year 2026-27) is that the combined loss among all local taxing districts in Oregon would be more than $20 million. The following year (tax year 2027-28), the statewide loss would escalate rapidly to more than $50 million. By the end of the decade, the annual revenue loss from a property tax freeze for seniors would approach $140 million.

The structure of the measure guarantees that the revenue losses will grow over time. In 1997, the enactment of Measure 50 severed the basis of property taxes from the traditional real market value to an “assessed value” that, generally speaking, may not grow by more than 3 percent per year. Except in the year Measure 50 took effect, the statewide total of assessed value has increased each year. Every year of eligibility, the difference between the assessed value under Measure 50 and the frozen level under the tax freeze grows, increasing the property tax loss to the local taxing jurisdiction.

Demographic changes will exacerbate the revenue loss — an aggravating factor not reflected in the revenue estimates above. Like the country as a whole, Oregon’s population is aging. The share of Oregon’s population 65 and older is projected to rise from 18.6 percent in 2021 to 24.2 percent by 2050. As the share of the population 65 and older increases, so too does the number of Oregonians potentially eligible for the property tax freeze as well as the loss of revenue to pay for local services.

Inequality

Oregon’s housing crisis is especially severe for renters, and yet the proposed senior property tax freezes exclude them and their landlords from any benefit. Renters tend to have lower incomes than homeowners, and housing costs weigh more heavily on renters than homeowners. These proposals would further tilt the tax code in favor of homeowners over renters. Both the federal tax code and the Oregon tax code provide significant tax benefits to homeowners, including the ability to deduct interest on a mortgage and property taxes.

Oregonians living below the poverty line are much less likely to benefit from the proposed senior property tax freezes than people living above it. Specifically, about 12 percent of Oregonians in poverty would be eligible for the property tax freeze, compared to 23 percent of Oregonians not in poverty. In other words, people living in poverty are about half as likely to benefit as people who do not live in poverty.

The proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors disproportionately favor white Oregonians, thereby worsening long-standing economic inequality by race. Black and brown Oregonians are significantly less likely to own a home than white Oregonians. Not only are Black and brown Oregonians less likely to own a home, but they also tend to have lower incomes and lower levels of wealth, and are more likely to be housing insecure.

Compounded Unfairness

The proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors would worsen the problem of horizontal inequity that already plagues Oregon’s property tax system. It is a basic principle of tax fairness that the tax system should treat similarly situated people the same. In the context of the property tax, this means that two properties worth the same should be taxed equally. Oregon’s property tax system already fails this test of fairness, and these proposals would make matters worse.

The existing horizontal inequities arise out of Measure 50. It severed property tax rates from real market value, tying the property’s assessed value — the basis for determining property taxes — to the real market value of the property as it stood in 1996 (minus a 10 percent discount). Since the enactment of Measure 50 in 1997, the assessed value of a property, generally speaking, has risen by no more than 3 percent, even if the real market value of the property has gone up more than that. Inevitably, this has resulted in homes that today have equal market value paying different property tax rates, or even more expensive homes paying lower property tax rates than less expensive homes.

Proposals to freeze seniors’ property taxes would create yet another layer of horizontal inequity. By freezing property taxes for some homeowners, it would lead to more situations where owners of homes with the same or even higher real market value pay a lower property tax rate than an owner of a home with the same or lower real market value.

For the full report, open this link:

Property Tax Freeze for Seniors Erodes Funding for Local Services and Worsens Inequities

Comment:

Daniel Hauser presents a detailed and cogent argument against both the proposed senior property tax assessment freeze and Oregon’s broken property tax system warped and baked into the constitution by Measures 5 and 50.

Why would lawmakers want to devise another system of tax breaks that compounds the inequities already present in the property tax system since 1996? The losers again would be lower income seniors, racial minorities, and renters not receiving any of the ‘benefits’ of the tax break.

Unfortunately there has been a trend across the country of using the tax system to reduce tax burdens for homeowners and giving venture capitalists financial rewards to reduce the cost of constructing new buildings. Using the tax system in this way results in the loss of revenue needed for schools and local infrastructure and services.

Rather let us encourage lawmakers to use a more imaginative approach to offering incentives to building investors and financial relief to cost burdened households.

First, fix Oregon’s broken property tax system by giving local jurisdictions a chance to opt out of M5 and M50 and adopt a local option Land Value Tax (LVT). Land and improvements are each appraised by county assessors using different methods for a good reason: they are entirely different components of real property. Unlike building value that arises from private capital investments, land value represents the speculative dimension of real estate. LVT applies differential rates to the total assessment.

Capturing land value through taxation is like an unearned increment tax, and is based on the premise that property owners benefiting from locational advantage should pay some portion of the cost of public improvements from which that value is derived. Building value, on the other hand, is created by the owner who invests in capital improvements, thus should remain with the owner.

Because the long term trend in real estate has shown substantial land price inflation, homeowners have been seeing significant equity build-up. The additional value from land can either be retained by individual owners as a capitalized asset, or returned to the public sector for the public good. A basic principle in liberal economics holds that legitimately created value belongs to the creator of that value. Hence, government is justified in recapturing what it has given. The split-rate land value tax achieves this objective.

We need to change our ideas about what is equitable taxation. If tax relief is based on an ability to pay criterion, the proposed senior property assessment freeze at its core violates this norm. The equity criterion for property taxation in particular is better achieved through tax payment in proportion to benefits received. Property owners’ benefits are in the form of ‘economic rent’ which can be measured as the cumulative gain in land value between the assessed land value at the time of purchase and the time of sale. A targeted tax exemption based on financial means is less suitable than a broad based tax on recapturing what the community has created and given.

In this way LVT captures the cumulated unearned increment, and leaves in the hands of owners the building value created by their own efforts through property upkeep and improvements.

Thus, we prefer a property tax deferral rather than an exemption. This will achieve the dual objectives of returning to the public sector revenues in proportion to benefits received and retaining the development incentives built into the LVT system. Also, public revenue losses can be avoided if relief were in the form of a deferral – making the tax obligation due at the point of resale when the accumulated home equity is liquidated.

Finally, instead of piling up more tax abatement programs for real estate investors, let’s use the built-in incentives of LVT to encourage new building investment.

As a result of placing proportionately higher taxes on land, it would become more costly to hold onto vacant or underutilized centrally located sites. Because the tax rate on buildings is lower, landowners have a strong incentive to increase the ratio of improvements to land assessments on their property. Investing in substantial capital improvements will produce income to offset higher taxes. A trend would emerge, opening sites for infill development with more compact, affordable development. LVT reduces speculation thus dampening land price inflation.

Tom Gihring, Research Director

Common Ground, OR/WA