The Forgotten Philosopher Who Can Fix Our Economy

Henry George has much to teach us about power and privilege today.

Joseph Addington

Writes Progress and Poverty

July 25, 2022

Excerpts:

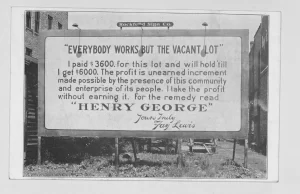

Postcard featuring a quote from Henry George, 1900. From the New York Public Library. (Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images).

We live in tumultuous times. Rampant social unrest, political instability, and rising populist anger have combined to create a particularly difficult cultural moment. Much of this is motivated by an increase in economic inequality, which in recent years has reached levels not seen since before the Great Depression. Social mobility has decreased. Housing—or, more specifically, land for housing—has become so expensive that many young people wonder if they will ever be able to afford a home at all. Many people have begun to feel that the American dream is dying, that the system is rigged, and that a better life is out of reach.

In many ways, our situation resembles the Gilded Age, a period during the late 19th century in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution. One Gilded Age figure who has important lessons for today is Henry George. A journalist and political economist, he has inspired millions worldwide to fight for a freer and more just society.

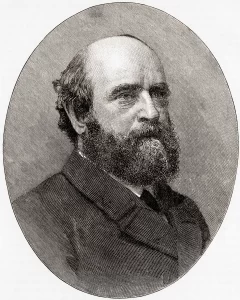

Henry George (Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

By the time of his death in 1897, Henry George was one of the most influential men in the Western world. He was the best-selling American economist ever published. George contemplated the great questions that bedeviled the Gilded Age. If technology was improving and productivity increasing—if more wealth was being generated faster than ever before—why was there so much abject poverty?

George realized that the problem lay in the monopolization of the Earth. The value of urbanization and technological progress was being captured by private land ownership. As technology improved and urbanization increased, the value of the land also increased. The result was soaring land rents, which soaked up the gains in productivity, leaving workers impoverished. (“Rent” here refers to the wealth and advantages derived from control over a scarce resource, as opposed to the colloquial use of “rent” meaning money paid to lease housing.) The primary beneficiaries of this process were landowners, who could extract more value from both workers and businesses who needed access to the land to live or set up shop, without the landowners providing any positive contribution to the economy themselves.

In 1879, George published a book titled Progress and Poverty, in which he built on the work of earlier liberals to argue that the Earth and its natural resources belong to mankind in common. Simply put, George believed that people own what they create with their labor. Because no-one created the land, the land belongs to everyone in common. But the absolute necessity of land for human life, both to live and to work, allows landowners to extract immense amounts of wealth from workers and business owners by charging for access. This activity incentivizes speculation, prices people out of their homes, makes it more difficult to operate a business, and creates decaying cities and urban sprawl. When land is monopolized in this way, the rents it produces enrich the landowners at the expense of society and cause seemingly intractable poverty.

The remedy George suggested was simple: replacing other taxes with a Land Value Tax (LVT). LTV is a tax on the unimproved value of land. It is premised on the idea that taxing the value of land prevents rent-seeking and speculation while unleashing the productive capacities of the economy. Unlike [conventional] property taxes which punish development, LVT incentivizes landowners to put land to productive use because the tax remains the same no matter how the land is used. Productive use can include using the land for commercial purposes, building housing on it, or selling it to others who will use it.

Furthermore, land value taxes fall solely on the owners of the land, who find it much harder to pass the burden of the tax onto their tenants. This is because landlords charge the highest price the rental market can bear, which is determined by supply and demand. Because an LVT doesn’t impact the supply of land, and doesn’t cause any rise in rental demand, the market for rents does not shift in response to the introduction of an LVT.

Henry George and the “Single Taxers,” as his followers called themselves, were not advocating for anything novel. In fact, they drew on a rich tradition of American and English liberalism to make their case. Liberals and proto-liberals from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill fought against concentrated land ownership. In the U.S., Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine advocated for a taxation of land values.

His argument was that classical liberalism was incomplete. It had managed to break the political power of the aristocracy by stripping them of their unique political privileges—but it had left intact the economic privileges of landlordism and monopolies which had allowed them to accumulate that power in the first place.

Land remains one of the biggest sources of rent extraction in the modern economy. A modern LVT would replace inefficient sales, property, income, and capital gains taxes, eliminating the penalties that the state levies on people who create a successful business or build a home.

Georgism can help heal our fractured republic and appeal to both sides of the political spectrum. It provides an alternative to the scarcity mindset by unleashing the productive forces of the economy, unburdened by punitive taxation. Most importantly, it can help treat the poison of populism at its root: the feeling that America doesn’t work for the average American anymore.

As George wrote in 1879:

Liberty calls to us again…Either we must wholly accept her or she will not stay. It is not enough that men should vote; it is not enough that they should be theoretically equal before the law. They must have liberty to avail themselves of the opportunities and means of life; they must stand on equal terms with reference to the bounty of nature. Either this, or Liberty withdraws her light…Unless its foundations be laid in justice, the social structure cannot stand.

—Henry George, Progress and Poverty.

Joseph Addington is the managing editor of the Substack Progress & Poverty and president of Young Georgists of America.

Comment:

Our research at Common Ground OR/WA reveals the high cost LVT imposes on landowners who hold land without using it. Changing the conventional property tax to a land-based tax reverses the incentive effect – from extracting windfalls to investing in new or upgraded buildings.

Tom Gihring, Research Director

Common Ground OR-WA