Check out this blog post from the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis about the housing market in Oregon and who benefits from the status quo. Comments below…

Who Benefits from the Housing Market?

Posted by: Josh Lehner | March 16, 2021

Excerpts:

One of the darker, underlying currents to the housing discussion is something along the lines that it’s the builders and developers who benefit the most, often described as exploiting or eroding our livability and quality of life. Usually this is couched in, shall we say, more colorful language. But it is a fairly pervasive element and ties in with neighborhood character and how we’d like folks to build housing over there, not here, or at this price point, not that price point, and so on.

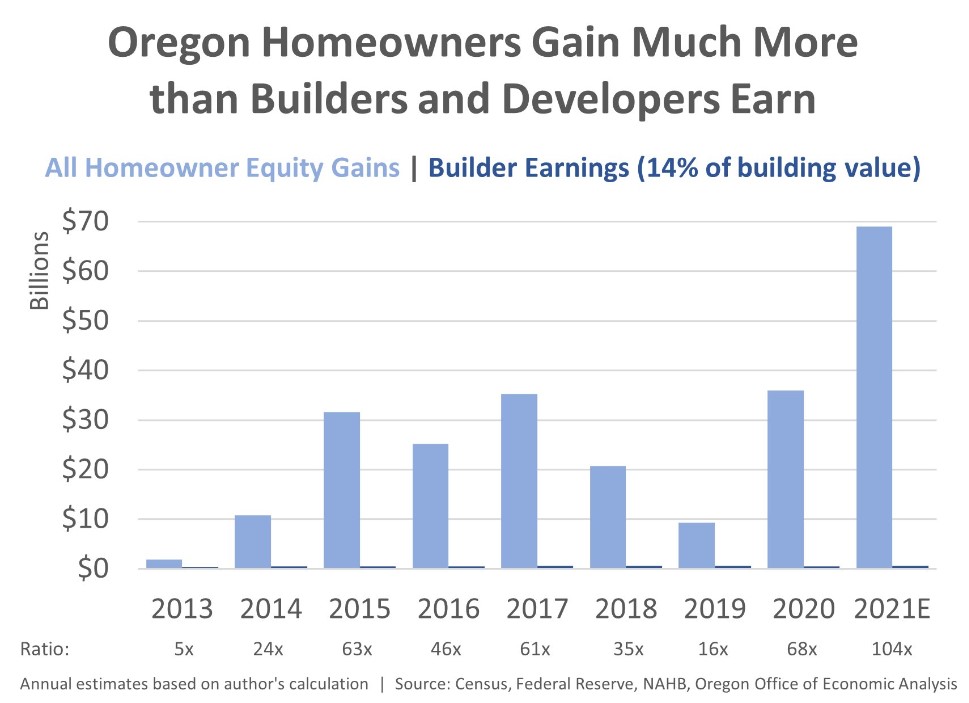

With this in mind, let’s take a quick look in this edition of the Graph of the Week of who benefits the most from the housing market. Long story short, local homeowners gain significantly more than builders and developers earn on their projects. In the past handful of years this ratio is about 40 to 1, depending upon how you want to talk about builder earnings. In short, builders and developers across Oregon are earning hundreds of millions of dollars a year, and homeowners are gaining tens of billions of dollars in equity a year.

Of course this is a bit of an apples to oranges comparison. Builder earnings are a flow based on new construction, which is equal to about 1% growth in the housing stock a year in recent years. Home equity is a stock that accrues to the million plus homeowners statewide as prices have risen by 7-8% on average over the same time period. However the figures are interwoven when new housing supply does not keep pace with demand. Even as developers may benefit from building more units at higher prices, the gains still accrue much more to our neighbors who happen to already own their home.

Housing wealth isn’t bad in and of itself. It’s used by families to build savings, to support spending, including remodels and start-up capital for new businesses. See our previous look at housing wealth for more. The issues arise when these dynamics worsen affordability, and price out our friends, family, and neighbors. Our office’s longstanding concern has been twofold. First there is the direct household budgetary impact on existing residents struggling to make ends meet. Second is the possibility that affordability may slow migration in the years ahead. Some would say, that’s good news, but if demand remains strong in the face of low supply and rising prices, we know who loses: those least able to afford it. Plus slower population growth means slower increases in the workforce that local businesses rely on to hire and expand.

Comment:

“Homeowners gain significantly more than builders and developers”. Consequently, homebuilders have been trying to improve their profit margins by opening up raw land in exurban greenfields where land prices are still low, erecting new buildings at the premium price segment of the housing market. As Lehner illustrates above, this only passes the increases in external costs of ownership onto suburban households.

On the other hand, homeowners are gaining “tens of billions of dollars in equity a year”, not from the structures on their lots, but rather from the land itself. Expectation of equity build-up is propelling land speculation, which is what is driving up housing prices. A widespread notion is that households want to sell their property to garner wealth for their families (Portland Tribune, January 19, 2022). Housing, rather than regarded primarily as shelter, has become a commodity. Ultimately, no one benefits from this scenario, especially newly forming households or those near the bottom of the income scale, and as long as existing homeowners continue moving into replacement housing.

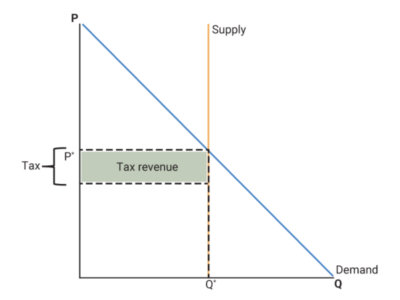

The better choice for both builders and residents is to open up centrally located sites where densities are higher and accessibility is much greater – where affordable housing options are most likely available. But how, when the upward pressure on land prices is so high? The answer can be found in the local property tax structure. A tax regime that raises the tax rate on land values and lowers the rate on improvements will dampen land price inflation and reward building investment – producing more housing.

Yes, this tax reform measure will shrink those billions of dollars of home “equity” (actually windfall from land value gains, termed “land rent”) that homeowners receive without contributing any labor or investment dollars. But is that really confiscatory, an undue seizure? No, because land value derives from the community at large: public infrastructure, accessibility, and natural amenities, and should ideally be returned to the creator of that value and used to provide public benefits. There is no natural right to extract wealth from land rent, an unearned increment.

Well, does this mean I lose all financial benefits from homeownership? Consider this: If a land value tax were chosen as a local option in Multnomah County, for instance, it would be introduced on a revenue neutral basis. That is total revenue collected is the same as under the existing tax system. We can then calculate how much of any property’s land value gain over one year is captured by the land value tax*.

Our recent analysis of home prices in Inner Northeast Portland neighborhoods found the hypothetical land rent tax capture rate to range between 16 and 23 percent for the average single family property. This means that a land value tax will leave over three quarters of the land value gain in the hands of the owner. The model traced recent trends wherein annual home price increases vary from about 8 to 12 percent. The capture rate is lower on properties whose home prices increase more rapidly; yet the LVT levy on these same properties is higher than the levy on lower growth properties when compared to a conventional equal rate tax levy. Also, let’s face it, such escalating values are unsustainable over the long run. Imagine the land value gain and capture rate this past year when home prices in a quarter of all U.S. metro areas spiked by more than 20 percent, and 80% grew at least by 10 percent.

*in this analysis 90% of the total tax rate is applied to land assessment, 10% on building value.

At these growth rates a land value tax that captures most or all of a homeowner’s land rent would have to far exceed revenue neutrality – even to the extent of replacing the state income tax and business taxes as well. Actually, from a Georgist perspective this would be a good idea. The income tax is inferior to a land value tax because it does nothing to encourage capital investment. An income tax will not bring idle urban land back into use. Only a land value tax will encourage highest and best use of land and discourage land speculation.

Another non-revenue neutral approach already in place is a tax on the extraction of natural resources, a form of LVT. Alaska state revenues from oil extraction have paid for public works and government services, and there is still a surplus. This excess revenue is distributed as a ‘dividend’ to residents on a per capita basis. “We’re taking wealth that belongs to the people… some call this socialistic, but it really is very conservative”, said former Republican governor Jay Hammond.

We need to reconsider whether fueling skyrocketing housing values is a good way to build personal wealth.

Tom Gihring,

Research Director, Common Ground OR-WA