Saumik Narayanan @ Streets.MN provides a great piece on why Minneapolis should implement a land value tax. Read on…

Why Minneapolis Needs a Land Value Tax

by Saumik Narayanan

August 28, 2020

Excerpt:

This image shows a mostly undeveloped parking lot, occupying a full block of prime real estate in the heart of downtown Minneapolis. Why does this lot remain underdeveloped? The owner of the land could increase their income drastically if they developed the land to its fullest potential. Additionally, the city as a whole would gain significantly from a more productive use of the land.

For example, a new apartment building could help increase housing stock in a city in the midst of an affordable housing crisis. More office space would increase the tax base by bringing in new workers to downtown, while new commercial businesses could easily serve thousands of existing residents thanks to the lot’s central location and easy access to transit. Building a new park in this space would add more greenery to the city and give the 50,000 downtown residents a new place to relax. And if the owners thought that parking was the best usage of the plot, a new parking ramp would still be a better use than a flat lot.

So if the landowner and the city both stand to gain from new development, why doesn’t development happen? One of the biggest reasons is that our tax code actually discourages new construction from taking place, in the form of property tax. Just the threat alone of an increased tax burden can make it unprofitable to construct new and useful developments.

Fortunately, there is a better way — the land value tax. Popularized by the American economist and politician Henry George, the land value tax has been advocated for by Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Adam Smith, among others. It has support from across the political aisle. The conservative icon Milton Friedman famously called it the “least bad tax,” while Joesph Stiglitz wrote that a land value tax would “would reduce inequality and… enhance growth.” Mentions of an LVT date back even to ancient India!

What is a Land Value Tax?

To explain how a land value tax works, it’s easiest to compare it to property taxes. When properties are assessed for taxes, the total value of the property is taxed at a flat rate. To get the total value of the property, the value is split up into two amounts: the value of the land itself and the improvements that are built on top of the land.

For example, the IDS Center in downtown Minneapolis has a land value of $25,233,700, and an improvement (building) value of $278,971,300, giving us a total market value of $304,205,000. With a traditional property tax, both the land value and improvements value are taxed at equal rates. A 3.7 percent property tax would mean the IDS must pay about $11 million a year in taxes. However, using a land value tax means only the land value ($25,233,700) is taxed, and the value of the improvements ($278,971,300) is left untaxed.

Why do we want to leave the value of the improvements untaxed? Essentially, choosing not to tax improvements removes an extra cost associated with building improvements, and makes it much easier and more profitable to actually build new developments. Take the vacant lot pictured above. Because there isn’t much built here, the majority of the property value consists solely of the land value, and the property tax ends up being very light, under $500,000. However, what if the parking lot owner wants to redevelop into something better? Here’s a quote from the owner of the lot in question:

“There isn’t any, I believe, surface parking lot owner in the city of Minneapolis that would rather have a surface parking lot as opposed to having the next IDS Center built on his or her piece of real estate … If there is somebody who thought they could make money on an office building, there would be an office building under construction.”

If any landowner wants to redevelop their property to increase usage, the city should welcome that idea with open arms. Instead our current tax code actually discourages it from happening. A hypothetical new office building at this space might project to bring in $5 million a year in increased profit, after accounting for construction and maintenance costs. However, if the amount of property tax goes up by $6 million (the amount that the office building across the street currently pays), then the developer would actually lose money on the new building, and it would be better for them not to build it at all.

To alleviate this issue, authorities may occasionally grant tax abatements, but it is more equitable and simple just to grant this tax reprieve in the form of eliminating property tax. With just a land value tax, no new costs would be associated with the office building, so it becomes viable for the lot owners. As a result, the lot owners gain by improving their income, other companies in downtown gain through the benefits of agglomeration, and the city’s economy grows thanks to the increased utilization of land overall. Everybody wins!

Although empty parking lots present the most obvious case of how removing the improvement tax rewards productive land use, this same shift in the cost-benefit analysis happens with development at all levels. In a city using land value taxes, building a residential duplex or triplex might be more viable than a single-family home, a proposal for a six-story apartment building could now become more profitable as an eight-story building, and businesses of all sizes will be free to redevelop extra, unneeded parking space. Even if we look at residential housing at the individual level, a land value tax removes disincentives for people to take better care of their property. With a land value tax, the owners of an unmaintained, run-down home would be encouraged to improve their home, since they would have no tax burden from any of the renovations.

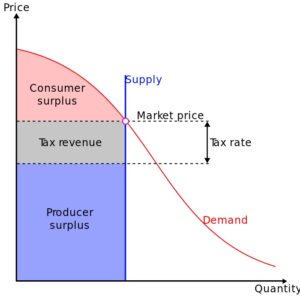

A graph showing how land value taxes cannot be passed on from landlords to renters

Other Benefits

Other than incentivizing development and good land use, land value taxes have a few other notable benefits:

- LVT is progressive. Because the supply of land is inelastic, it is impossible to pass on an LVT from landlords to renters or consumers, unlike property tax.

- LVT is difficult to evade. Companies and individuals might be able to shift all their income to the Cayman Islands, but they will have to leave their land behind.

- LVT minimizes the downsides of the economic boom/bust cycle, since it discourages land speculation.

Thanks to Kelvin Liu for his help in collaborating and editing this article.

from https://streets.mn/