Prosper Australia

Speculation, housing supply and prices

by Tim Helm | Jul 24, 2023 | Progress Magazine

A summary of recent research

Speculation: it’s a Georgist obsession shared by few others. Landbanking, flipping, vacancy, delayed development, staged releases – how does any of this matter?

Excerpts

Speculative behaviour tells of the market at work, allocating capital and land as it sees fit. What is the public interest in these private decisions? Why do [Georgists] care about speculation? Because we care about housing supply and affordability, and because we care about economic justice.

Prosper’s research over the last 12 months has had a sharp focus on these topics. Georgists appreciate the centrality of speculation to land markets and the centrality of land markets to economic justice in ways others do not. Our work has begun to unpack these connections, examining land markets from different angles, and laying these ideas out for a public audience.

Increasingly dominant in public discourse is a worldview in which unaffordable housing is declared a problem of housing costs – not population, incomes, or inequality – and in which housing costs are declared a problem of public regulation – not private markets. The prices aren’t right, the problem is on the supply side, and the fault lies with the state, we are told.

Prosper’s concern with this is twofold.

First, deregulating land use – the go-to solution for the neo-neo-liberals – means granting windfalls to private landowners. Property titles are a bundle of rights; add more to the bundle and its value rises. But so long as employers are taxed for employing and workers are taxed for working, where is the justice in landowners becoming rich through no effort of their own?

Our work points towards a simple axiom for policy change: if there is upzoning aimed at boosting housing supply, let it not occur without value capture. Georgist taxation can thus promote distributional justice.

Second, pinning the blame on regulation ignores the mass of evidence that private markets constrain housing supply all on their own. We call that speculation: rational delay in developing already-profitable projects.

In explaining housing supply and the dynamics of land markets we see speculation not as a footnote but as a feature, an empirical fact that economic science must contend with, and cannot assume away. Our work points towards another simple axiom for policy: since housing supply only begins when land speculation ends, use the right taxes to end speculation. Georgist taxation can thus promote economic prosperity.

Since the last edition of Progress, Prosper’s staff and research network have explored different aspects, which we summarise here.

Staged releases: Peering behind the land supply curtain

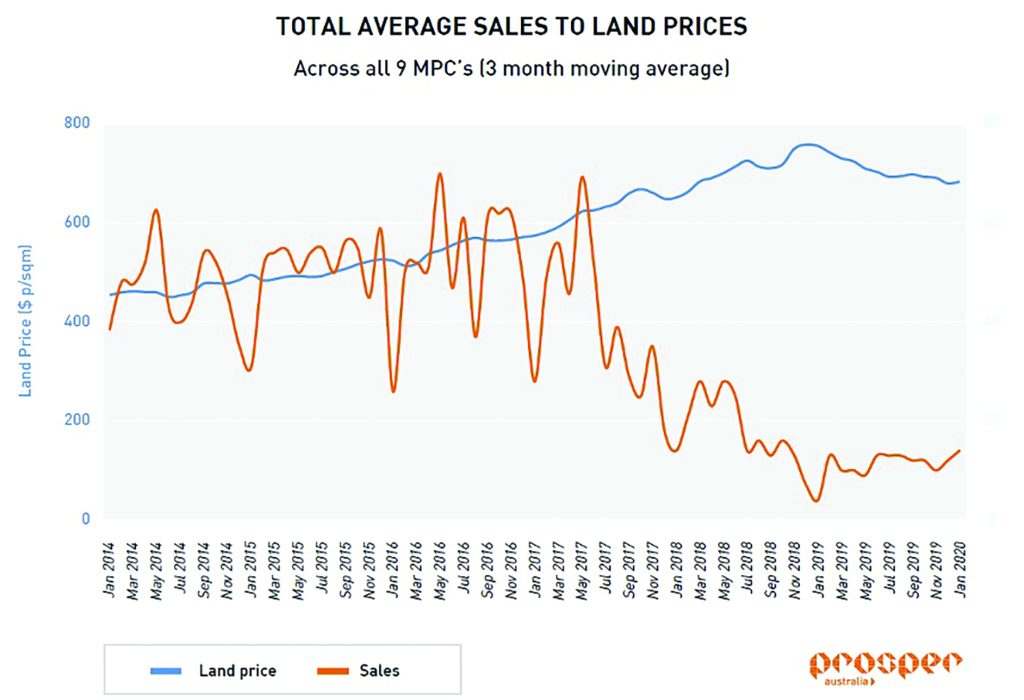

In his final report for Prosper, released in July 2022, Karl Fitzgerald investigated the rate of lot sales in major master-planned housing developments. His report revealed a “staged release” strategy in which sales rates respond positively to price growth but are slowed when necessary to avoid causing supply-led price declines.

Based on records of over 25,000 sales across nine subdivisions, the report examined the speed at which properties were released to the market, the determinants of those sales rates, and the resulting pricing outcomes.

After an average 10 years of production time, the subdivision developers in the study still held an average three-quarters of their land bank vacant, pointing to an expected total development time frame of 40 years on average.

Instead of land prices falling with such massive supply capacities at hand, they grew by a sobering 5.5% per annum in real terms. Sales rates varied significantly according to market conditions, with faster sales when the market was running hot and markedly lower rates as the market cooled. Developers preferred to continue pushing prices higher, letting sales rates drop, than to maintain sales by lowering prices.

During these periods developers also reported concerns of “stock overhang” to investors, indicating that they were able to sell more, but unwilling to reduce prices to do so. Instead, they preferred to wait for market conditions to improve. This pricing and sales response reflects an approach that serves shareholders and financiers, but not the public interest in lower land prices. Land banking of this type holds the promise of supply-led affordability at bay.

Sales to Land Prices

How could this occur? What explains this behaviour?

Land prices are not grounded in any kind of cost. Developers selling serviced lots set prices to meet the market, not to recover the costs of labour and capital inputs, as in ordinary industrial production. Why would the developers in Prosper’s report keep increasing prices if it meant losing sales or market share? And what does it say about our ability to ‘flood the market’ with zoned capacity in order to lower prices that the recipients of these rights refuse to flood the market with land for housing?

It suggests that unlike markets for goods and services, property markets are inherently monopolistic, and cannot be made more competitive. This was always the classical understanding: Smith, Ricardo, Mill and George would have found the idea of “competitive land markets” a bemusing oxymoron. As leading legal scholar Eric Posner puts it, “property is only another name for monopoly”. Land is not the output of a production process, but is an asset, and is managed as such. This was borne out in the report data: land banks were patiently drip-fed to market, with development projects timed to maximise overall returns.

The report’s findings sound a cautionary note for policymakers placing market supply at the centre of housing policy, suggesting the most effective means of promoting more affordable housing is not on the supply side, but on the income side.

_________________________________________________

Comment:

The important point made here in this excerpted first section of the Prosper article is that land is not the output of a production process, but is an asset (and as we say: ‘a gift of nature’). This is where the Georgist solution corresponds. Simple logic reveals that taxing something results in less of it. If we want to encourage production (housing units) we would untax building investment in new construction. On the other hand, land being an asset not resulting from any labor or productive activity, it is fair to tax its value. In fact, land value is an unearned increment, and as we learned is purely speculative. If we want to increase building supply and decrease rising land prices, raise the tax rate on land and decrease the tax rate on improvements. That’s LVT – land value taxation, promoted twelve decades ago by political economist Henry George.

For an overview of Prosper Australia’s tax reform agenda, see the paper: A tax Shift for Our Future.

Tom Gihring, Research Director

Common Ground, OR/WA