Portland Business Tribune

Report: More Portlanders struggling with home costs despite “affordable housing” increase

Jim Redden Mar 23, 2023

Excerpts:

The Portland Housing Bureau has opened a record number of government-supported housing units for families earning less than the area median income. But Portlanders who do not qualify for such housing are having a harder time finding an affordable place to live.

This is the main takeaway from the “2022 State of Housing in Portland” report released by the bureau on Wednesday, March 22. It found that despite unprecedented growth in the construction of so-called affordable housing projects, most Portlanders are having a harder time meeting increasing rents or mortgage payments.

“This year’s report comes at a critical time in Portland’s housing landscape. While the city continues to grapple with the lingering effects of the pandemic, an affordable housing shortage, deepening disparities, and a housing market that continues to leave nearly half of all renters cost-burdened, the city also faces a ‘perfect storm’ of market conditions that are making housing less affordable, including rising inflation and interest rates,” Housing Commissioner Carmen Rubio said in a release accompanying the report.

At the same time, from 2021 to 2022, average rents increased by 3.7 percent, and median home sale prices citywide increased 17 percent from 2016, reaching $525,000 in 2021. Meanwhile, rental vacancy rates have decreased from 6.4 percent in 2021 to 6 percent in 2022.

Half of all Portland renters are cost burdened, paying over 30% of their income in rent. 1 in 4 pays over half their income in rent,” the release said.

The release said the report is only one step in efforts by Rubio’s office and various bureaus “to better understand and address the complex issues contributing to Portland’s housing crisis.” During this calendar year, they will be conducting studies and issuing reports on: the overarching cost drivers in housing; local cost drivers compared to other cities; the performance of the Inclusionary Housing policy; and the types of housing Portlanders will need. This foundational work will build into the development of a housing production strategy led by the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability later this year.

_______________________________________

Comments:

Indeed, the situation is becoming worse as housing prices continue their upward trajectory. In Metro Portland, median home price jumped in one year (2021 to 2022) by 12.7 percent.

In Portland city, the average rental charge for a 2 bedroom apartment was 1,895 in 2022, and the median income for a 4 person household in the Portland SMSA was $106,500. This rent-to-income ratio is well affordable, but for a low income household it is not. At 50% of median income, the R/I ratio is 43%, well above the 30% ratio most landlords would require. The HUD limits for a 2 BR apartment for the 50% MI group is a monthly rent of $1,198.

The slow housing construction rate we’ve experienced during the past several years is pushing down vacancy rates, while the demand for multifamily housing is steadily increasing. This drives up rents, leading newly forming households and first time buyers to seek apartments in distant suburbs where prices are marginally lower.

Meantime, outside real estate investors are buying up existing housing units. Across the U.S., investors purchased nearly a fifth of all homes sold in the last quarter of 2021. In Portland, investors such as Cascade Home Buyers LLC and Spartan Redevelopment purchased an eighth of the homes sold in that period, mostly in low and middle-income neighborhoods. Reselling within a year, these “flippers” often sell to other investors who then rent out the homes charging higher rates. Other investors in the Portland area are buying up existing multifamily complexes “with upside potential”, making upgrades to the structures, thereby “increasing the value of the assets”. All this activity leads to higher profits for investors and decreasing affordability for occupants.

“Most Portlanders are having a harder time meeting increasing rents or mortgage payments”. What then is the solution to this problem? Increase housing supply? Build more government-subsidized housing? Increase rental assistance, thereby closing the gap in the rent-to-income ratio?

First, the supply-demand view may be a useful way to explain short-term spikes in housing prices, but it is not a particularly useful way of addressing the housing affordability problem. Unaffordability has been a long-term trend since the late 1970’s, and can be described as a growing gap between rapidly rising housing costs and diminishing household incomes. Increasing the supply of housing itself will not bring housing into the range of affordability, as builders will by inherently build at the highest price point the private market will bear. One way to defuse this delayed action time bomb is to remove a substantial share of the existing housing stock from the private speculative market into public ownership, as well as non-profit ownership such as community land trusts. But this alone may not be sustainable in the long run. Why?

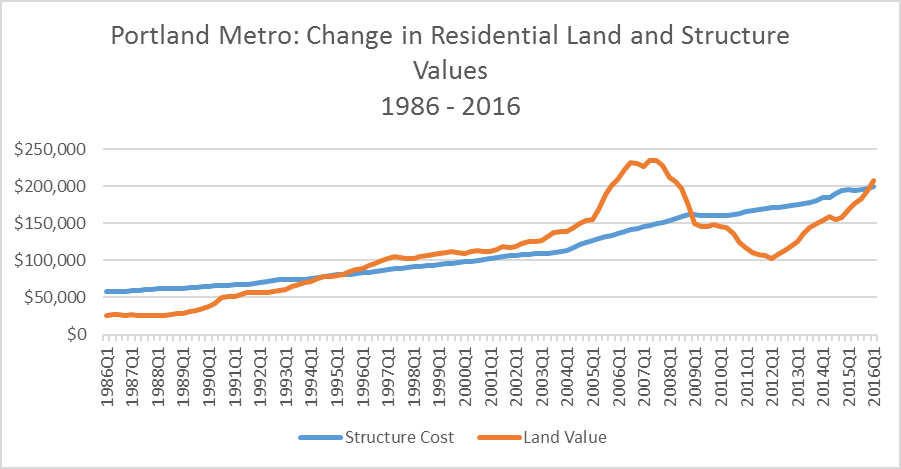

To understand how housing costs have gotten out of hand it is necessary to look at not only houses and apartments but also the land beneath them. Over several decades the price of building materials and construction labor have increased at about the level of the consumer price index, or the rate of general inflation. On the other hand, residential land prices have soared far above general inflation.

In regional housing markets across North America, there is strong evidence that rising residential land prices are largely responsible for driving the increase in housing costs.

Data source: Davis, Morris A. and Michael G. Palumbo, 2007, “The Price of Residential Land in Large US Cities”

The rapid rise in land prices since the 1970’s is to a large degree a function of the “commodification” of housing—the inclination to maximize equity by trading up homes and seeking new locations which increase the most in value. Not only do existing homeowners expect to capture the cumulative equity in their homes, but the real estate investment industry has also jumped into the monetizing game by buying up homes low and selling (or renting) high.

Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley inveighed : “the costs of both renting and buying homes are rapidly increasing – hurting ordinary people so investors can get rich. In every corner of the country, giant financial corporations are buying up housing and driving up both rents and home prices. Not only do these hedge funds and private equity firms outbid ordinary Americans looking to buy homes, they just care about squeezing as much profit as they can out of the properties they own. Wall Street is pouring fuel on the fire of the affordable housing crisis.”

As the private housing market is geared to pushing up speculative land value, it becomes clear why non-profits like King County Habitat for Humanity are moving away from its traditional build mode of single-family homes, and instead seeking sites for multi-unit buildings. The estimated median lot value in Seattle is about $334,000 – far beyond the price range for building a typical Habitat family home.

Affordability over the long run can only be sustained by intentionally holding down land prices which are the biggest driver of escalating housing costs. Increasing the building supply can’t bring down land prices, but the property tax does have that potential. Unfortunately, in Oregon our existing property tax system is diametrically counter to this objective. The Oregon Tax Revolt, which started in 1990 with the enactment of Measure 5 and then Measure 50 in 1997, created an exceptionally unfair tax system. M-50 prevents a property’s assessed value from increasing more than 3% per year, creating a “split roll” separating maximum assessed values (MAV) from real market values (RMV). Over time, as land values have rapidly increased (except during the great recession), the gap between MAV and RMV has steadily widened.

Rather than holding down land prices, the Oregon tax does just the opposite. Several analytical reports, including those by the Legislative Revenue Office, have documented the perverse incentives and inequities of the property tax system. Staff at the Portland Housing Bureau may recall the study conducted by Northwest Economic Research Center (NERC) investigating the effect of the property tax structure on residential sales prices, specifically the magnitude of tax capitalization. “We found that differences in property tax payments are having a significant effect on sale price”. Buyers may prefer houses built before 1996 when M-50 took effect because property taxes will be much lower than comparable newer properties. The selling prices of these houses will therefore be higher as the low tax payments are capitalized into added value, creating windfalls for the owners when they sell.

The advantage to long-time owners is compounded: they benefit from low tax payments while occupying their homes, and they gain a price advantage when they sell. The result is two houses in different locations, similar in structure and real market value assessment, diverge substantially in taxes levied and potential sales price. “You might be paying four times more than another home across town that’s worth the same amount”. The low tax benefits primarily accrue to higher income owners in rapidly appreciating neighborhoods. Equally detrimental, landowners/speculators often gain the most by leaving their urban land empty or buildings neglected. Even as land value steadily increases in the surrounding area, annual taxes are depressed on these properties because improvement values are minimal. Letting structures deteriorate, holding land out of production, and thus constricting available land supply, is rewarded by Oregon’s broken property tax system.

As to the second point, increasing rental assistance, the principal tool has been the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, supported by the federal government and operated by the state. It first launched in 1986, becoming permanent in 1993. With the LIHTC, property investor owners get a tax break lasting between 10 and 60 years, depending on the project. In exchange, they reserve some of their units for low-income renters for the designated period. Now, Oregon Housing and Community Services estimates that the low-income requirements for about 4,400 units will expire within the next 8 years. What happens when over four thousand affordable units are converted to market rate by their owners? In the likely scenario, Oregon state taxpayers will be asked to pick up the tab for either gap financing of new affordable housing construction or rental assistance or relocation payment programs. But subsidies are a stop-gap solution because taxpayers will eventually grow weary of forever paying for other’s basic shelter needs.

A survey from the Oregon Values and Beliefs Center asked respondents about social services needed across the state. More people said they would prefer the government to provide incentives for the private sector to address the state’s housing shortage than for the state to address it directly. It appears that Oregonians are not favorable to continuous subsidies for affordable housing. They would instead “empower” housing providers with financial incentives not funded by taxpayers – not “top-down charity”. (printed in the Portland Tribune, November 30, 2022)

Are financial incentives a realistic solution to the housing crisis? In a word yes.

If Oregon would change its dysfunctional property tax system to a land value tax (LVT), the incentive effects would reverse. The ‘single tax’ political economist Henry George in the 1890s argued that taxes should be shifted to land and away from labor and productive capital. With land heavily taxed, it would be in the interests of landowners to find the most productive use for it. It would also mean that inflation of land prices would be mitigated, as land purchasers would know that heavy taxes come with holding land.

The modern version of LVT usually occurs as a split-rate tax. The fiscal impact on individual parcels depends on the land share of its total property value. Any property with a higher than the county average proportion of value in land will pay a higher effective tax under LVT. A simultaneous change from the current MAV to RMV assessments as the basis for the split rate tax corrects the disparity of the current system. The capitalization effect is inverted; higher taxes on land are capitalized into a lower selling price. Rapid land value growth neighborhoods will experience a rise in tax burden, and low growth neighborhoods a decrease. LVT is revenue neutral; there is no revenue loss, no subsidy.

Tax incidence studies show consistently that LVT affords the biggest advantage to the multifamily land use category. Habitat Seattle as a case in point stands to benefit by making the choice of placing a larger number of dwelling units on a lot, thus making more efficient use of land, and lowering its tax levy. The most recent NERC study in Multnomah County makes this clear. Because the land-to-total value ratio of multifamily properties (.24) is lower than the total county ratio (.40), the tax shift is negative. When changing from the current tax system to LVT, multi-family developments of more than 4 units will see a 16% reduction in tax bills in inner northeast Portland where land values have been rising rapidly, and a 36% reduction in low value growth in outer southeast neighborhoods.

The NERC model simulations demonstrate that ultimately the land-based property tax system will achieve what it is designed to do—remove the unfair tax advantage from wealthier landowners, provide a more equitable tax structure, incentivize building upgrading and development of underutilized properties, discourage “holding” land for speculative purposes, and encourage the highest and best use of land.

Commissioner Rubio’s office would like “to better understand and address the complex issues contributing to Portland’s housing crisis,” and will be conducting studies and issuing reports on the overarching cost drivers in housing. We hope that a clearer understanding of land price inflation and the mitigating effects of a reformed state tax structure will support this effort.

Tom Gihring, Research Director

Common Ground – OR/WA