Our Sightline Institute friends reported on Portland’s new zoning rules allowing “missing middle” housing on single family lots.

See an excerpt of this article…

Portland Just Passed The Best Low-Density Zoning Reform in US History

The reform sets a new standard: up to four homes on almost any lot, or up to six homes for price-regulated projects.

By Michael Andersen (@andersem)

August 11, 2020, at 3:01 pm

Portland’s city council set a new bar for North American housing reform by legalizing up to four homes on almost any residential lot.

Portland’s new rules will also offer a “deeper affordability” option: four to six homes on any lot if at least half are available to low-income Portlanders at regulated, affordable prices. The measure will make it viable for nonprofits to intersperse below-market housing anywhere in the city for the first time in a century.

The “Residential Infill Project,” RIP as it’s known, melds ideas pioneered recently by Minneapolis and Austin and goes well beyond the requirements of a state law Oregon passed last year. It’s the most pro-housing reform to low-density zones in US history.

In 2019, Oregon’s legislature took up the issue, led by a former fourplex resident: Portland-based House Speaker Tina Kotek. That led to a groundbreaking state law legalizing “middle housing” of up to four homes throughout the Portland metro area but stopping short of allowing it on any lot.

Early in 2020, Wheeler still couldn’t find the votes for the local reform—until another pair of hours-long hearings, in which pro-housing voices led by the advocacy groups Portland: Neighbors Welcome and Anti-Displacement PDX united around the concepts of adding the “deeper affordability” sixplex amendment and simultaneously pursuing other tenant protections like Eudaly’s “tenant opportunity to purchase” concept. At those hearings, pro-housing testimony outnumbered anti-housing testimony more than six to one.

Throughout the process, the backers were a coalition of affordable housing developers like Hacienda Community Development, stable-housing advocates like the Cully Housing Action Team, environmentalists like Sunrise PDX, justice advocates like AARP Oregon, civic groups like the Northeast Coalition of Neighborhoods, transportation reformers like Oregon Walks, and dozens of active volunteers, with years of staffed organizing work by the anti-sprawl nonprofit 1000 Friends of Oregon and, later, us at Sightline.

This Follows and Surpasses Reforms in Other Cities

Portland’s reform will build on similar actions in Vancouver and Minneapolis, whose leaders voted in 2018 to re-legalize duplexes and triplexes, respectively; in Seattle, where a 2019 reform to accessory cottages resulted in something very close to citywide triplex legalization; and in Austin, whose council passed a very similar sixplex-with-affordability proposal in 2019.

But Portland’s changes are likely to gradually result in more actual homes than any of those milestone reforms.

That’s because in both Vancouver and Minneapolis, city laws in low-density zones cap the size of new buildings no matter how many homes they create. In Minneapolis, for example, the interior square footage of a building can be up to half the square footage of its lot: 2,500 square feet of housing on a hypothetical 5,000 square foot lot.

Portland’s new rules set that same size limit for one-unit buildings. But Portland’s duplexes will be up to three-fifths the square footage of their lot, and triplexes and fourplexes up to 0.7.

The idea is for that extra square footage to work like a sluice gate for Portland’s housing market, rechanneling investment away from luxury remodels and McMansions and toward new homes that are affordable to the middle class on day one. Low-density parts of Vancouver and Minneapolis currently have no such distinctions.

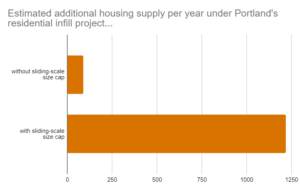

Image by Sightline Institute. Source: Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability.

As we wrote in January, legalizing simplexes for regulated-affordable projects is the economic equivalent of cutting a check for $100,000 or more per affordable home. It alone may not be enough to make those homes appear, but it makes every existing subsidy go further. And it doesn’t take a dime away from other existing programs.

Just as importantly, it makes it feasible for builders like Habitat to gradually scatter such projects through all Portland neighborhoods. It lifts a de facto ban on new affordable housing from much of the city.

So-called “missing middle” housing options like triplexes, courtyard apartments and cottages aren’t radical or even unfamiliar. They’re just scarce—because they’ve been largely banned from cities across Cascadia and the rest of the US and Canada. In Portland, the bans began in 1924 and expanded almost citywide in 1959. Almost every city in either country that’s existed for more than a century has a similar story.

One effect, in many cities a primary goal, was to segregate people by class, race, age and income. But that wasn’t the only effect—bans on the lowest-cost way to create new homes accidentally created scarcity for everyone.

Is it good to have a diversity of housing types and prices in every neighborhood? Or is it bad?

In the last two years, the Democratic Party has rapidly come around to the position that it’s good. Its presidential candidate’s platform reflects this: Joe Biden says the federal government should withhold various grants from cities that don’t take steps toward the standard Portland is about to set.

________________________________________________

Comments:

This is the biggest rewrite of Portland’s zoning code since 1991. The City opened residential neighborhoods to accessory dwelling units (ADU) in 1981, and in 1991 allowed duplexes on corners.

Now because of RIP, over the next 20 years up to 24,000 more households will be able to live in one of Portland’s “complete” walkable neighborhoods, close to transit, parks, shops and other amenities.

Market-rate fourplexes tend to be cheaper than market-rate duplexes or triplexes. Below-market fourplexes require less subsidy than below-market duplexes or triplexes. Not only does an affordable housing developer like Habitat for Humanity get to split the land cost four ways, they also spread the costs of converting property into one or more condos, and site preparation.

And, perhaps most importantly, RIP opens the opportunity to leverage the positive incentives of a local option land value tax. More building volume on a land parcel raises the ratio of building value to land value. The new zoning allows internal floor space to reach up to 70 percent of the lot area. Because the split-rate LVT raises the tax rate on land assessment, simultaneously lowering the rate on improvement assessment, the revised property tax burden is lower than the conventional equal rate tax burden. In fact, the current system would significantly increase taxes on property owners who take advantage of this opportunity to add to the supply of affordable housing. That is the perverse incentive built into our broken property tax structure! Time for the state legislature to legalize LVT!