Progress and Poverty

Land and Liberty to Build: On Georgism and YIMBYism

Only an alliance of Georgism and YIMBYism is capable of addressing rising housing costs and economic inequality

Stephen Hoskins Sep 19, 2022

Excerpts

Introduction

Spend any time trying to untangle the Gordian knot of urban housing costs and you’ll quickly encounter two groups claiming to hold the scissors: the YIMBYs and the Georgists. YIMBYs (‘Yes-In-My-Back-Yard’) argue that cutting land use regulations (’upzoning’) will boost housing construction and improve affordability; while Georgists believe we should shift the tax base onto land, to punish the speculative under-use of urban lots and stimulate the supply of homes. While many folks agree with both positions and there is much overlap between the two groups, they sometimes lob criticisms at one another and often vie for primacy in the housing discourse.

In this article, I will argue that both upzoning and land value tax are absolutely necessary if we want to fix our cities. I’ll explain why they are natural allies in the fight against landed interests, and demonstrate that they are so much better together. All urbanists should adopt both as a core tenet of their advocacy.

Why Georgists should also be YIMBYs

While George’s lifetime predated our Euclidean system of zoning, it is clear that he would have found it an abhorrent barrier to human freedom. His single tax advocacy ultimately sought to liberate individuals from the extractive burden of land rents, thus providing freedom to all. Freedom to George meant an ardent opposition to all regulations “save those required for public health, safety, morals and convenience”, which clearly excludes our burdensome zoning. George wields this principle most directly in Protection or Free Trade, arguing that trade tariffs protect companies from competition, and grant them monopolistic power to raise prices, hurting consumers. In an identical manner, zoning is a regulatory tax on production which grants landowners the right to exclude others from their community and ultimately curtails our freedom to live and work on land in the manner that best serves human need.

Zoning which limits the densification of urban areas, like height limits, setbacks and maximum floor area ratios, acts as a stifling handbrake on the dynamism of our cities and banishes us to suburban isolation. Low-income folks are hurt most by this exclusion, exacerbating inequality. YIMBY upzoning would not just improve social mobility and equality, but will also weaken both racial and economic segregation within cities.

Georgists should be appalled by zoning which forces households to over-consume land, such as minimum lot sizes, minimum parking requirements, and use restrictions that separate where we live from where we work and play. These force cities to sprawl outwards, undermining the viability of public transit and increasing carbon emissions through car-centric commutes and less energy-efficient dwellings.

Why YIMBYs should also be Georgists

YIMBY readers may be clapping along in agreement that upzoning can solve many of our social woes. But without incorporating the lessons of Georgism, many of the benefits of upzoning will be slow to materialize and will flow straight into the pockets of landlords.

For the owners of upzoned land in desirable locations, YIMBYism can be incredibly lucrative. Relaxing a height limit multiplies the rental income that can be earned from building upward on a piece of land. Landowners know this and respond by demanding much higher prices from developers trying to acquire their land for construction. Thus, upzoning can instantly raise the value of upzoned land. A huge portion of what we call ‘developers’ are really just speculative land bankers who buy sites, lobby for upzoning, and then make-off with their ill-gotten windfall gains, without actually adding to the supply of housing.

…we must find ways to capture the value that is created by upzoning so it can benefit everyone in society, not just lucky landowners. Upzoning paired with a windfall gains tax can help share the land rents created by upzoning. Land value tax (LVT) ensures that whoever benefits most from zoning will also contribute the most taxes. Even better, by placing a price on land banking, it will nudge developers back into the business of building.

Imposing an annual LVT ensures that landowners bear the full opportunity cost of holding land, increasing the cost of delayed development, ultimately increasing the rate of supply. Again, we see that the benefits of YIMBYism are supercharged by LVT.

…the ultimate outcome of YIMBY advocacy could actually be a world where the largest volume of land rents flow from tenants to landlords. Georgist land policy redirects these rents back into the hands of the public, and prevents YIMBYism from accidentally exacerbating land’s central role in inequality.

The Georgist solution here is essential: use LVT to capture the benefits of thriving urban areas, and redistribute the revenues, so that every single member of society gets to share in the benefits created by upzoning and urban intensification.

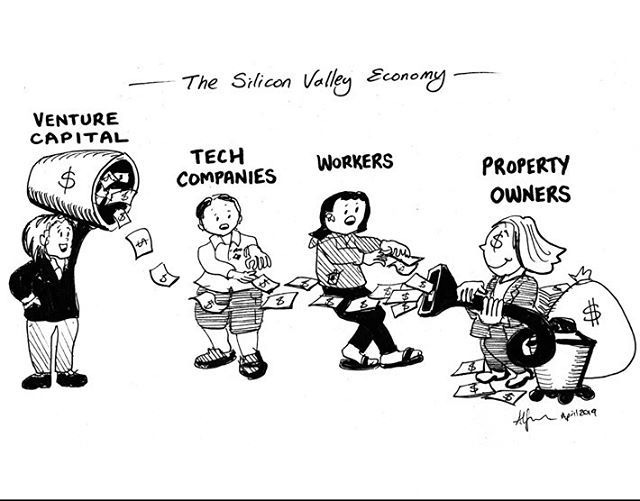

The Silicon Valley Economy, comic by Alfred Twu

The Great LVT-YIMBY Symbiosis

Upzoning and land value capture are both absolutely essential policies in our combat against the crisis of crushing housing costs. But they are even better together. Both Georgists and YIMBYs should be pursuing a symbiotic marriage of the two movements. We share so many of the same objectives: efficient use of land, affordable housing, thriving cities, urban intensification around walkable mixed-use neighborhoods, and we all want to undermine the exclusionary power of urban landowners.

While LVT will stop speculation in its tracks, a failure to accommodate the endless demand for access to urban locations will leave many of society’s most vulnerable locked out of the places where they would have the most opportunity. Upzoning and intensification are critical components of our pressing need to slow climate change.

And while YIMBY may remove the legal barriers to dense housing, LVT will ensure that it actually gets built. Without policies to punish land speculation, urban intensification will fail to materialize, and any benefits of upzoning will flow straight into the hands of urban landowners. LVT with YIMBY gets us the densification we desperately need, and shares the prosperity gains among all.

Where to from here?

Privatized land rents and exclusionary zoning are the most destructive union of political interests of our time, and all urban advocates should embrace any and all opportunities to undermine either. YIMBY groups should place land value capture at the core of their policy objectives. Georgists should support YIMBY efforts to intensify cities and stress that LVT can both boost and broaden the benefits of upzoning.

Wherever possible, we should support housing policy that dulls landowners’ financial interest in speculation and exclusion, by zoning for density and producing competing supply via public & third-sector providers. We must use the tax system to discourage land banking, and punish the speculative under-utilization of valuable urban sites, by taxing land value and capturing the windfalls from rezoning or public investment.

We face a generation beset by rising inequality and increasing rents. Millions will, without a significant change in our land use policies, be locked out of the places that provide them with the most opportunity. If we do not take the necessary steps to liberate our cities from the twin scourges of rentierism and NIMBYism, we will condemn ourselves and those who will come after us to a cycle of poverty, exclusion and extraction. Georgists and YIMBYs must urgently forge their alliance. Only by so doing can we create a nation with a place for all.

________________________________

Comment:

We at Common Ground OR/WA are in full agreement with the basic premise of Hoskin’s article that up-zoning and land value taxation working in concert can be an effective means to curb land speculation and increase development opportunities. There are a few points, however, that could be clarified. First, it seems that Hoskin conflates the broad term ‘zoning’ with exclusionary zoning. If he had used the qualifying term, we would agree that it is discriminatory and forces owners to overconsume land.

Secondly, it is not accurate to say that Henry George opposed all regulations “save those required for public health, safety, morals and convenience”, which clearly excludes burdensome zoning. Actually the protection of public health, safety, and public welfare (expressed as the ‘Police Power’) does include zoning. Historically it was and still is the legal basis for zoning as a regulatory tool. The original declared purpose was to prevent (by segregating land uses) harm from nearby toxic uses, and to ensure (through building setbacks) adequate light and air in crowded living accommodations. Zoning, however, did evolved into an exclusionary tool (elevating the primacy of single family homes) which we agree is a regulatory tax which grants landowners the right to exclude others from their community.

Thirdly, we question the blanket assertion that up-zoning can instantly raise the value of up-zoned land. Our own research in inner northeast Portland, Oregon, yields no evidence of land value increase on residential properties recently up-zoned to duplex, and 3-plex housing. Here, it important to distinguish between up-zoning in concentrated areas and broad scale up-zoning to moderate densities throughout much of the city, which is the case in Portland. In this case, redevelopment opportunities are present, but will in reality occur only gradually and in scattered locations. The impact on land value in any single location is too diluted to affect a significant change.

We do agree that because ubiquitous single family zoning limits the supply of multifamily development opportunities, and the demand for housing units is high, residential land values throughout the entire city will rise. And we also recognize the solution is predicated on both broad scale up-zoning and the availability of redevelopable sites. It is the land value tax that will raise the cost of landholding and release more sites for redevelopment, giving the greatest benefit in tax discounts to multifamily housing types. Will LVT stop speculation in its tracks? If the split tax rate differential weighs heavily on land, the prospects are hopeful.

Tom Gihring, Research Director

Common Ground – OR/WA