Mythbusting Carbon Tax Myths

The entrenched power of the fossil-fuel industry and its political backers isn’t all that stands in the way of taxes on carbon pollution. Outmoded ideas and enduring myths about energy use and taxes are also factors.

This page describes and dissects some of these misconceptions. Please send us your own favorite fallacies about carbon taxes. Ditto your suggestions or criticisms of ours.

Myth #1. A tax on carbon pollution will harm the poor and middle class.

Who says? Some low-income advocates, some left-of-center activists, some conservatives masking as populists.

Rebuttal: The wealthy use more carbon-based energy than the rest of us, by far. For every gallon of gasoline used by the poorest quintile (20%) of households, the richest quintile uses three.

A similar pattern holds for the other sources of carbon pollution: electricity, jet fuel, even diesel fuel that powers the trucks that deliver goods. It’s true that consumption taxes, a category including carbon taxes, are “regressive” — they take a larger share of income from low-income households — but that’s true only when the use of the tax revenues is ignored. The net impact can be made “progressive,” i.e., beneficial to people of below-average means, by proper distribution of those revenues.

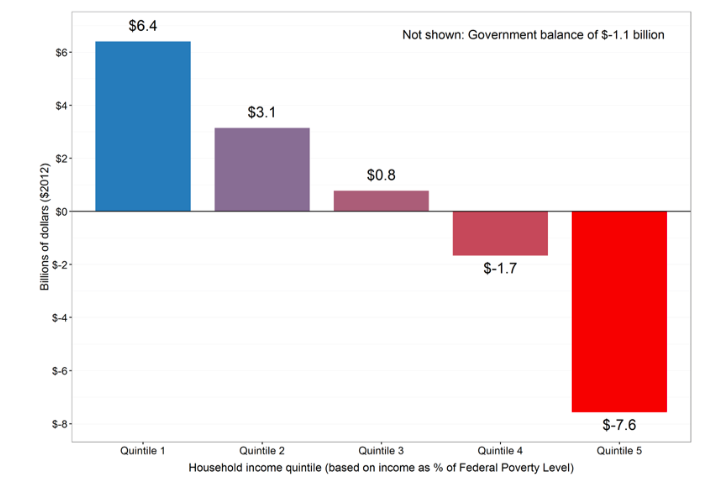

One policy option is to distribute the revenue directly to households as regular “dividends.” Climate scientist Jim Hansen and the Citizens Climate Lobby are among those calling for all carbon tax revenues to be returned to citizens in equal, monthly “green checks.” In 2016 CCL released a working paper analyzing the short-term financial impact of a $15/ton carbon fee under this plan.

The report, which estimated household carbon footprints with new levels of detail, including crucial geographical variation, found that 53% of U.S. households (58% of individuals) would reap a positive net financial benefit, i.e., receiving more via the dividends than they would pay directly and indirectly in higher fossil fuel prices. The benefits would be greatest for lower-income, younger, senior, and minority households with nearly 90% of households below the poverty line benefitting from a carbon tax. The distributional effect would essentially shift purchasing power from the top quintile of households to the bottom two quintiles, highlighting the income-progressive nature of a fee-and-dividend plan.

A worthy alternative, which Al Gore and many economists advocate, is “tax-shifting” — use carbon tax revenues to reduce regressive taxes such as sales taxes and payroll taxes. (See our Issues page, Managing Impacts.) British Columbia has enacted and annually increased its revenue-neutral carbon tax with popular support by dedicating all revenue to reducing a variety of other taxes ranging from sales taxes to business taxes.

What’s really regressive is the impact of global warming. Sea level rise, food shortages and storms like Katrina, Irene and Sandy hit the poorest hardest.

Myth #2. Carbon taxes won’t change habits — after all, high gasoline prices haven’t cut usage.

Who says? An odd collection of groups and individuals, including former Sierra Club “CAFE” (car fuel-economy) lobbyist Dan Becker (“Even as gas prices have doubled and trebled over the past several years, we see little change in driving behavior,” Becker told the New York Times in October, 2006.)

Rebuttal: Four points are key. First, rises in gasoline prices have cut usage, and by more than a little. Comparing 2008, the last pre-recession year, to 2003, U.S. gasoline usage was unchanged even though economic activity was up 13%. What did the trick was the 73% higher price “real” (inflation-adjusted) price. Second, much of the increase in energy prices in recent years was masked by price volatility; as we show here, over the past decade or more, gas prices have fallen almost as often on a month-to-month basis as they have risen, masking the upward trend and convincing millions of Americans that prices would head south soon enough to make adjustments unnecessary. Third, other sectors, especially electricity generation, which emits nearly twice as much CO2 as cars, are even more price-sensitive. Last, price-responsiveness will grow as households have opportunities to buy more fuel-efficient vehicles and appliances, and as society transitions to a more fuel-efficient infrastructure — once we enact carbon taxes to send clear and strong price signals. (See our Issues page, Carbon Tax Effectiveness, for more discussion.)

Myth #3. Taxes on carbon emissions aren’t necessary. Vehicle efficiency standards and mandates or subsidies for wind turbines, ethanol, hydrogen, nuclear power [pick one or more] will solve the problem.

Who says? Special interests, many environmental groups, security advocates, technology buffs.

Rebuttal: Standards and subsidies are blunt instruments — vehicle efficiency standards don’t reduce vehicle usage, for example — and are often contested for years and then undermined by “gaming” (viz., the “light trucks” exemption from CAFE standards, or tax credits for hybrid SUV’s). Moreover, fuel usage is ever-changing and diffuse (a majority of petroleum is not used in cars or light trucks, for example), while efficiency standards are by nature both usage-specific and frozen in time. As for supply, economic theory predicts, and experience confirms, that raising the price of a harmful activity is always more effective at reducing that activity than is lowering prices of the thousands of imaginable alternatives — as we documented in the comments we submitted in January 2014 to the Senate Finance Committee. Only taxes on carbon pollution from fossil fuels can create the clear, rapid, across-the-board incentives needed to propel a massive shift to clean alternatives.

Other Resources:

The Case for a Carbon Tax (by Prof. Shi-Ling Hsu), reviewed here. Chapter 4 offers forceful responses to standard (and largely mythological) arguments against carbon taxes and chapter 5 delves into some of the psychology that biases many people against using price instruments to address global warming.