IS A LAND VALUE TAX RIGHT FOR RICHMOND, VIRGINIA?

Purpose of this Report

This report provides the results of a preliminary analysis to determine the on-the-ground effects of implementing a land value tax (LVT) in Richmond Virginia. While the findings contained herein give an accurate representation of changes in the general tax trends within the City that will result from the adoption of an LVT, CPTR recommends the conduct of a series of more detailed analyses to determine parcel-level and other effects before proceeding with adjustments to existing property tax codes, and is prepared to carry out this work with the participation and support of the City of Richmond.

Who We Are

A joint effort of the Center for the Study of Economics and the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, the Center for Property Tax Reform (CPTR) is a nonprofit research center dedicated to understanding the effects, strengths, and weaknesses of property taxes at the local level. We work with elected officials and other community leaders and use current assessment data to determine whether a switch to a land value-focused approach to taxation will benefit local residents and businesses while encouraging healthy development and redevelopment patterns. Our staff include Ph.D. and Master’s level researchers with over 50 years combined experience in issues of taxation, land use, and public policy.

What is LVT?

LVT is an approach to property taxation that places all or most of the tax burden on land values, leaving the value of improvements (like people’s homes and businesses) completely or largely untaxed. LVT can be implemented using current assessment data, so “start up” costs and timelines are minimal. This tax policy is usually more progressive than a traditional property tax, and has been shown in recent academic studies to produce a variety of positive outcomes, including increased residential and commercial real estate values, reductions in rates of tax delinquency, and infill development combined with reduced pressure for new development at the periphery, all without diminishing overall tax revenues to the City.

Research Methods

The findings presented here are based on the most recent tax assessment data for Richmond. CPTR researchers accessed these data as a GIS shapefile from the City’s open site in July, 2021, and using mapping and statistical software, identified the property-class level effects of moving from the current property tax structure to an LVT. Additional studies are required to determine parcel-level impacts; tax progressivity; opportunities to reduce other local, deadweight loss-inducing taxes through adoption of an LVT; and other, place-specific effects of interest. CPTR researchers are prepared to conduct these additional studies with input and support from municipal partners in Richmond.

Research Findings

The analysis described here was designed to be revenue neutral, ensuring that while the sources of the tax dollars may shift under an LVT, revenue totals do not.

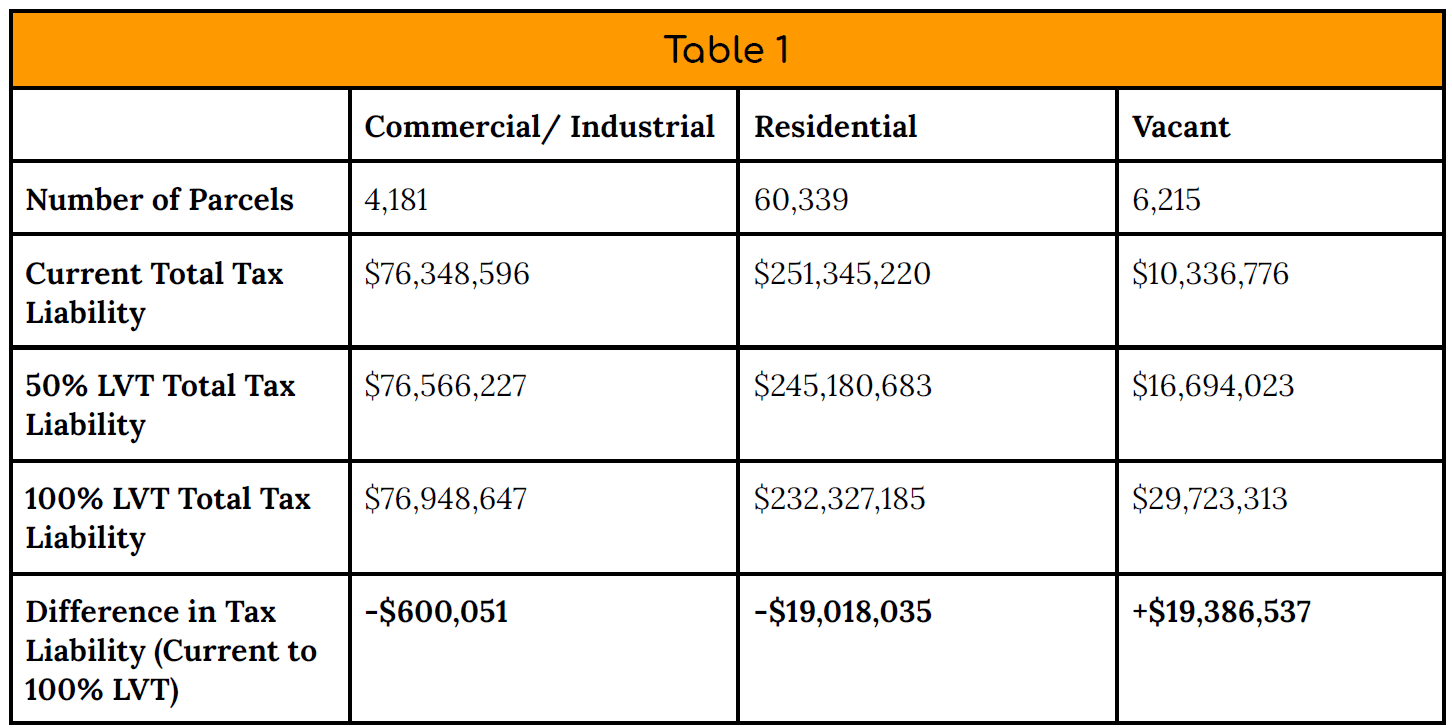

In 2020, Richmond’s total property tax revenue was just over $338M. This sum is raised by applying the City’s property tax rate of 1.2% to the assessed value of the structures (which constitute about 74% of total property value in the jurisdiction) and land (the remaining 26%). As Table 11 makes clear, shifting to a land value tax would yield appreciable benefits to residents, saving them nearly $6 million under a 50% LVT scenario, and over $19 million if 100% of revenues were generated through a tax on land. Commercial and industrial property owners will realize a modest savings (~$600K at 100% LVT) under these alternate taxing scenarios.

Conclusion

As CPTR’s preliminary analysis demonstrates, adoption of an LVT would yield tax savings for residents, while forcing the owners of vacant land to pay their fair share, incentivizing them to make the improvements necessary to warrant the higher holding costs of their properties, or sell to someone willing to make those much-needed investments in the City.

It should be noted that the findings presented here are preliminary. Additional studies are required to determine parcel-level impacts; tax progressivity; opportunities to reduce other local, deadweight loss-inducing taxes through adoption of an LVT; and other, place-specific effects of interest. CPTR researchers are prepared to conduct these additional studies with input and support from the City of Richmond.

Table 1 does not include data on a handful of property classes, such as “institutional,” “null,” and “public open space,” which represent very small segments of the overall taxable population. This (intentional) omission results in table totals which do not zero out.