A Tax that Would Solve the Housing Crisis

Eliminate all taxes but a levy on land, said Henry George. Here’s why it would work. Part one of three.

Henry George: ‘Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.’ Illustration by Walter Russell, Public Domain.

In Vancouver, responses to the housing crisis fall into two camps: there are those who would increase supply and those who would limit demand. Both points of view have merit and both are needed.

But mostly overlooked in this debate is the real problem. It’s not that houses cost a lot. They don’t. Building a house in Vancouver costs roughly the same per square foot as in 100 Mile House.

It’s the land under homes that cost a lot. And land, because they are not making any more of it, is particularly susceptible to speculative pressures.

This isn’t the first time that the cost of urban land has spiralled beyond the reach of average wage earners. During the last “Gilded Age,” between 1870 and the advent of the First World War, land prices also rose dramatically. A bold solution came out of that time, championed by a popular political economist.

His name was Henry George.

George and the Single Tax movement

Henry George was born in Philadelphia in 1839. He was the second of 10 children in a lower-middle-class family. George started off as a journalist, working mostly in California, but with a brief stint in Victoria during his 20s.

One day in 1871 on a horseback ride, he stopped to rest while overlooking San Francisco Bay. He met a teamster, and to make small talk, he asked how much land nearby was worth. The teamster didn’t know how much exactly, but said there was a local who was willing to sell his property for a $1,000 an acre.

It was an epiphany for George.

“Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth,” George later wrote. “With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.”

George would champion the Single Tax movement, which has renewed relevance today given how urban land values are pushing housing costs more and more out of reach. George argued for the elimination of income taxes, taxes on sales and taxes on productive capital like machinery or buildings.

There should only be one tax, George said, and that would be on land. To our modern ears this sounds irrational and our skepticism is largely a testament to how savagely his ideas were attacked at the time — an attack that endures to this day.

George’s hypothesis was this: land, since it gains its value passively (just by sitting there without adding anything to production), should be very heavily taxed. This would reduce or eliminate the tax burden on the labour of wage earners, the profit of owners and the buildings and machinery that makes production possible.

Reader, if you have a bit of exposure to political economy, you might recognize something unique about this formulation. While Marx pitted workers against owners, Henry George united them. To George, workers and owners were on the same side. By working together, both made the world a better and richer place.

The real drag on culture, George argued, were people whose gains came passively by just sitting on a resource, doing nothing to it as its value rose.

What George found most outrageous was that the value of any piece of urban land didn’t come from the effort of its owner; its value reflected past labour and enterprise performed on surrounding lands. Yet most of the gains from all this creative effort went to the land owner/speculator with very little to the people who actually created that value.

In the case of Vancouver, current land prices are high because of all the good work done and taxes paid by previous generations of citizens. But are these citizens or their children reaping any reward?

Most outrageously, land owners/speculators often gained the most by leaving their urban land empty and thus useless. Being useless, the land was often not taxed, even though its value steadily increased by the growth of the surrounding city.

George argued that taxes should be shifted to land and away from labour and productive capital. With land heavily taxed, it would be in the interests of land owners to find the most productive use for it. It would also mean that inflation of land prices would be mitigated, as land purchasers would know that heavy taxes came with owning land. Thus, the tax shift would both reduce taxes on productive activities and make land cheaper to put to productive use.

Reader, do you find George’s plan reasonable?

If so, you would join the many millions who agreed with George during his lifetime. He became famous throughout the English-speaking world before his life was cut short at 58 by a stroke. His book Progress and Poverty sold millions of copies, even outselling the Bible during all of the 1890s.

Is land a commodity?

But what happened to George’s ideas? Why didn’t they take hold?

George was fiercely opposed by the landed gentry of his time, the very same people — the Vanderbilts, the Rockefellers — who were gaining fantastic wealth through passive gains on land.

They responded to the Georgian surge by funding entire academic programs to crush the Single Tax movement’s popularity, paying carefully selected academics to muddy George’s case. One such program was the “Chicago school” at the University of Chicago, still a hugely influential source for conservative economic thought today (for example, the famous neoclassical economist Milton Friedman, economic adviser to both Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, taught there).

The Chicago school and other “liberal” think tanks successfully removed George’s qualitative distinction between land (in his view, inherently unproductive) and labour, enterprise, machinery and buildings (in George’s view, productive contributors to society).

Now, classical economists treat land as a form of capital, equal in productive value to other capital goods — such as apartment buildings, factories or railroad rolling stock. These economists were successful because the rest of us can no longer see the distinction between “passive” land and productive labour and capital. Without this distinction, our thinking is too muddled to see how land, in the hands of speculators, impedes the development of an equitable and productive Vancouver.

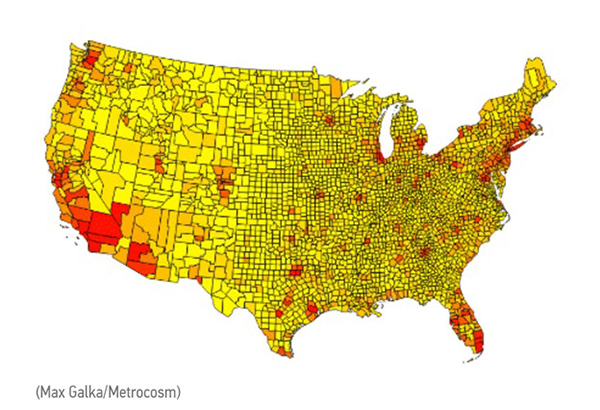

Figure 1. Map of the U.S. showing counties indicating value of land therein. As one would expect, urban areas have the highest value per county. Similar images are not available for Canada but would indicate the same patterns. Max Galka, Metrocosm.

Figure 2. Map of the U.S. showing the same information as in Figure 1, but with counties sized to conform with the total value of land in that county. The overwhelming value of urban lands is thus more clearly illustrated. Similar image for Canada not available but would show the same exaggerated pattern. Max Galka, Metrocosm.

No love for lazy land

Reader, if you’re with me so far, you’re ready for another word that has been exiled by classical economists: the rentier. The word rentier is also making a comeback, in line with the revival of Georgian thought. This is no surprise.

A rentier is one who gains wealth through passive actions. Land speculators, who add to their wealth by letting the value of land rise and/or collecting ever higher rents for the use of land, are rentiers.

The English landed gentry of yore were probably the most famous category of rentier. But the term applies to anyone who gains wealth passively. It’s a useful distinction, and one that we hear more and more.

The wealthy are often called “job creators” on the assumption that those who gain wealth do so through their investment of entrepreneurial energy and money into business activities. In the process, job creators provide work and income for wage earners.

Henry George would agree. He applauded the “job creators.”

But sadly, because of the work of classical economists, we lump active entrepreneurs together with passive rentiers. While it’s fair to celebrate Elon Musk and Steve Jobs for their success as job creators, it’s not so appealing to similarly celebrate those who passively use their wealth to acquire more wealth, a wealth that is typically taxed at a very low rate, if it is taxed at all.

In most countries, the largest tax burden falls onto the backs of wage earners in the form of income tax. Not very Georgian. Profits acquired through land sale are typically taxed at much lower capital gains rates, with advantageous real estate loopholes available to bring the tax burden on land sales to zero in many cases (for more see Trump, Donald J.).

Here in Vancouver, we see how land is increasingly forcing housing out of reach of wage earners and sapping the economic strength of the city. Productive, well-educated, creative wage earners can no longer afford to live here.

As they move away, the capacity of the city to generate new enterprise is also diminished. We are not just talking about high-tech startups, though they too are affected. We are talking about more mundane but crucial work in every field — from food services to teaching to law and medicine. The price of land has priced out every profession except real estate agents.

Vancouver is on track to become a place for the rich to park money and for the rest of us to visit as a tourist now and then — the Monaco of North America. A grim fate, but an avoidable one.

Henry George had it right.

For Vancouver to survive as anything other than a tourist resort we need to tax land to cut off fuel that feeds the fires of land speculation and use the proceeds to create secure housing for wage earners with ordinary incomes.

After taxing land, then what? Well, it’s time to move past the stigma of non-market housing and build it. Part two on the history of public housing in North America here. ![]()